Data Wants to Be Free: Fast Data Exchange with Apache Arrow

Published

28 Feb 2025

By

David Li, Ian Cook, Matt Topol

This is the second in a series of posts that aims to demystify the use of Arrow as a data interchange format for databases and query engines.

Posts in this series:

- How the Apache Arrow Format Accelerates Query Result Transfer

- Data Wants to Be Free: Fast Data Exchange with Apache Arrow

As data practitioners, we often find our data “held hostage”. Instead of being able to use data as soon as we get it, we have to spend time—time to parse and clean up inefficient and messy CSV files, time to wait for an outdated query engine to struggle with a few gigabytes of data, and time to wait for the data to make it across a socket. It’s that last point we’ll focus on today. In an age of multi-gigabit networks, why is it even a problem in the first place? And make no mistake, it is a problem—research by Mark Raasveldt and Hannes Mühleisen in their 2017 paper1 found that some systems take over ten minutes to transfer a dataset that should only take ten seconds2.

Why are we waiting 60 times as long as we need to? As we've argued before, serialization overheads plague our tools—and Arrow can help us here. So let’s make that more concrete: we’ll compare how PostgreSQL and Arrow encode the same data to illustrate the impact of the data serialization format. Then we’ll tour various ways to build protocols with Arrow, like Arrow HTTP and Arrow Flight, and how you might use each of them.

PostgreSQL vs Arrow: Data Serialization

Let’s compare the PostgreSQL binary format and Arrow IPC on the same dataset, and show how Arrow (with all the benefit of hindsight) makes better trade-offs than its predecessors.

When you execute a query with PostgreSQL, the client/driver uses the PostgreSQL wire protocol to send the query and get back the result. Inside that protocol, the result set is encoded with the PostgreSQL binary format3.

First, we’ll create a table and fill it with data:

postgres=# CREATE TABLE demo (id BIGINT, val TEXT, val2 BIGINT);

CREATE TABLE

postgres=# INSERT INTO demo VALUES (1, 'foo', 64), (2, 'a longer string', 128), (3, 'yet another string', 10);

INSERT 0 3

We can then use the COPY command to dump the raw binary data from PostgreSQL into a file:

postgres=# COPY demo TO '/tmp/demo.bin' WITH BINARY;

COPY 3

Then we can annotate the actual bytes of the data based on the documentation:

00000000: 50 47 43 4f 50 59 0a ff PGCOPY.. COPY signature, flags,

00000008: 0d 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ and extension

00000010: 00 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 ........ Values in row

00000018: 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ Length of value

00000020: 01 00 00 00 03 66 6f 6f .....foo Data

00000028: 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 00 ........

00000030: 00 00 00 40 00 03 00 00 ...@....

00000038: 00 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

00000040: 00 02 00 00 00 0f 61 20 ......a

00000048: 6c 6f 6e 67 65 72 20 73 longer s

00000050: 74 72 69 6e 67 00 00 00 tring...

00000058: 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

00000060: 80 00 03 00 00 00 08 00 ........

00000068: 00 00 00 00 00 00 03 00 ........

00000070: 00 00 12 79 65 74 20 61 ...yet a

00000078: 6e 6f 74 68 65 72 20 73 nother s

00000080: 74 72 69 6e 67 00 00 00 tring...

00000088: 08 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

00000090: 0a ff ff ... End of streamHonestly, PostgreSQL’s binary format is quite understandable, and compact at first glance. It's just a series of length-prefixed fields. But a closer look isn’t so favorable. PostgreSQL has overheads proportional to the number of rows and columns:

- Every row has a 2 byte prefix for the number of values in the row. But the data is tabular—we already know this info, and it doesn’t change!

- Every value of every row has a 4 byte prefix for the length of the following data, or -1 if the value is NULL. But we know the data types, and those don’t change—plus, values of most types have a fixed, known length!

- All values are big-endian. But most of our devices are little-endian, so the data has to be converted.

For example, a single column of int32 values would have 4 bytes of data and 6 bytes of overhead per row—60% is “wasted!”4 The ratio gets a little better with more columns (but not with more rows); in the limit we approach “only” 50% overhead. And then each of the values has to be converted (even if endian-swapping is trivial). To PostgreSQL’s credit, its format is at least cheap and easy to parse—other formats get fancy with tricks like “varint” encoding which are quite expensive.

How does Arrow compare? We can use ADBC to pull the PostgreSQL table into an Arrow table, then annotate it like before:

>>> import adbc_driver_postgresql.dbapi

>>> import pyarrow.ipc

>>> conn = adbc_driver_postgresql.dbapi.connect("...")

>>> cur = conn.cursor()

>>> cur.execute("SELECT * FROM demo")

>>> data = cur.fetchallarrow()

>>> writer = pyarrow.ipc.new_stream("demo.arrows", data.schema)

>>> writer.write_table(data)

>>> writer.close()

00000000: ff ff ff ff d8 00 00 00 ........ IPC message length

00000008: 10 00 00 00 00 00 0a 00 ........ IPC schema

⋮ (208 bytes)

000000e0: ff ff ff ff f8 00 00 00 ........ IPC message length

000000e8: 14 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ IPC record batch

⋮ (240 bytes)

000001e0: 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........ Data for column #1

000001e8: 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

000001f0: 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

000001f8: 00 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 ........ String offsets

00000200: 12 00 00 00 24 00 00 00 ....$...

00000208: 66 6f 6f 61 20 6c 6f 6e fooa lon Data for column #2

00000210: 67 65 72 20 73 74 72 69 ger stri

00000218: 6e 67 79 65 74 20 61 6e ngyet an

00000220: 6f 74 68 65 72 20 73 74 other st

00000228: 72 69 6e 67 00 00 00 00 ring.... Alignment padding

00000230: 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 @....... Data for column #3

00000238: 80 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

00000240: 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

00000248: ff ff ff ff 00 00 00 00 ........ IPC end-of-streamArrow looks quite…intimidating…at first glance. There’s a giant header that don’t seem related to our dataset at all, plus mysterious padding that seems to exist solely to take up space. But the important thing is that the overhead is fixed. Whether you’re transferring one row or a billion, the overhead doesn’t change. And unlike PostgreSQL, no per-value parsing is required.

Instead of putting lengths of values everywhere, Arrow groups values of the same column (and hence same type) together, so it just needs the length of the buffer5. Overhead isn't added where it isn't otherwise needed. Strings still have a length per value. Nullability is instead stored in a bitmap, which is omitted if there aren’t any NULL values (as it is here). Because of that, more rows of data doesn’t increase the overhead; instead, the more data you have, the less you pay.

Even the header isn’t actually the disadvantage it looks like. The header contains the schema, which makes the data stream self-describing. With PostgreSQL, you need to get the schema from somewhere else. So we aren’t making an apples-to-apples comparison in the first place: PostgreSQL still has to transfer the schema, it’s just not part of the “binary format” that we’re looking at here6.

There’s actually another problem with PostgreSQL: alignment. The 2 byte field count at the start of every row means all the 8 byte integers after it are unaligned. And that requires extra effort to handle properly (e.g. explicit unaligned load idioms), lest you suffer undefined behavior, a performance penalty, or even a runtime error. Arrow, on the other hand, strategically adds some padding to keep data aligned, and lets you use little-endian or big-endian byte order depending on your data. And Arrow doesn’t apply expensive encodings to the data that require further parsing. So generally, you can use Arrow data as-is without having to parse every value.

That’s the benefit of Arrow being a standardized data format. By using Arrow for serialization, data coming off the wire is already in Arrow format, and can furthermore be directly passed on to DuckDB, pandas, polars, cuDF, DataFusion, or any number of systems. Meanwhile, even if the PostgreSQL format addressed these problems—adding padding to align fields, using little-endian or making endianness configurable, trimming the overhead—you’d still end up having to convert the data to another format (probably Arrow) to use downstream.

Even if you really did want to use the PostgreSQL binary format everywhere7, the documentation rather unfortunately points you to the C source code as the documentation. Arrow, on the other hand, has a specification, documentation, and multiple implementations (including third-party ones) across a dozen languages for you to pick up and use in your own applications.

Now, we don’t mean to pick on PostgreSQL here. Obviously, PostgreSQL is a full-featured database with a storied history, a different set of goals and constraints than Arrow, and many happy users. Arrow isn’t trying to compete in that space. But their domains do intersect. PostgreSQL’s wire protocol has become a de facto standard, with even brand new products like Google’s AlloyDB using it, and so its design affects many projects8. In fact, AlloyDB is a great example of a shiny new columnar query engine being locked behind a row-oriented client protocol from the 90s. So Amdahl’s law rears its head again—optimizing the “front” and “back” of your data pipeline doesn’t matter when the middle is what's holding you back.

A quiver of Arrow (projects)

So if Arrow is so great, how can we actually use it to build our own protocols? Luckily, Arrow comes with a variety of building blocks for different situations.

- We just talked about Arrow IPC before. Where Arrow is the in-memory format defining how arrays of data are laid out, er, in memory, Arrow IPC defines how to serialize and deserialize Arrow data so it can be sent somewhere else—whether that means being written to a file, to a socket, into a shared buffer, or otherwise. Arrow IPC organizes data as a sequence of messages, making it easy to stream over your favorite transport, like WebSockets.

- Arrow HTTP is “just” streaming Arrow IPC over HTTP. The Arrow community is working on standardizing it, so that different clients agree on how exactly to do this. There’s examples of clients and servers across several languages, how to use HTTP Range requests, using multipart/mixed requests to send combined JSON and Arrow responses, and more. While not a full protocol in and of itself, it’ll fit right in when building REST APIs.

- Disassociated IPC combines Arrow IPC with advanced network transports like UCX and libfabric. For those who require the absolute best performance and have the specialized hardware to boot, this allows you to send Arrow data at full throttle, taking advantage of scatter-gather, Infiniband, and more.

- Arrow Flight SQL is a fully defined protocol for accessing relational databases. Think of it as an alternative to the full PostgreSQL wire protocol: it defines how to connect to a database, execute queries, fetch results, view the catalog, and so on. For database developers, Flight SQL provides a fully Arrow-native protocol with clients for several programming languages and drivers for ADBC, JDBC, and ODBC—all of which you don’t have to build yourself.

- And finally, ADBC actually isn’t a protocol. Instead, it’s an API abstraction layer for working with databases (like JDBC and ODBC—bet you didn’t see that coming), that’s Arrow-native and doesn’t require transposing or converting columnar data back and forth. ADBC gives you a single API to access data from multiple databases, whether they use Flight SQL or something else under the hood, and if a conversion is absolutely necessary, ADBC handles the details so that you don’t have to build out a dozen connectors on your own.

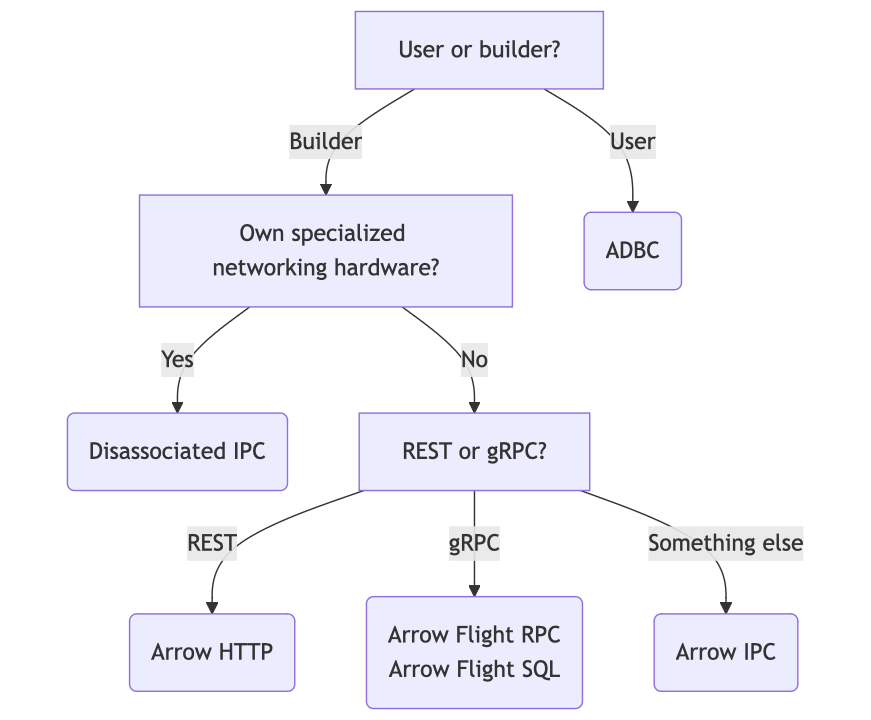

So to summarize:

- If you’re using a database or other data system, you want ADBC.

- If you’re building a database, you want Arrow Flight SQL.

- If you’re working with specialized networking hardware (you’ll know if you are—that stuff doesn’t come cheap), you want the Disassociated IPC Protocol.

- If you’re designing a REST-ish API, you want Arrow HTTP.

- And otherwise, you can roll-your-own with Arrow IPC.

{:class="img-responsive" width="100%"}

{:class="img-responsive" width="100%"}

Conclusion

Existing client protocols can be wasteful. Arrow offers better efficiency and avoids design pitfalls from the past. And Arrow makes it easy to build and consume data APIs with a variety of standards like Arrow IPC, Arrow HTTP, and ADBC. By using Arrow serialization in protocols, everyone benefits from easier, faster, and simpler data access, and we can avoid accidentally holding data captive behind slow and inefficient interfaces.

-

Figure 1 in the paper shows Hive and MongoDB taking over 600 seconds vs the baseline of 10 seconds for netcat to transfer the CSV file. Of course, that means the comparison is not entirely fair since the CSV file is not being parsed, but it gives an idea of the magnitudes involved. ↩

-

There is a text format too, and that is often the default used by many clients. We won't discuss it here. ↩

-

Of course, it’s not fully wasted, as null/not-null is data as well. But for accounting purposes, we’ll be consistent and call lengths, padding, bitmaps, etc. “overhead”. ↩

-

That's what's being stored in that ginormous header (among other things)—the lengths of all the buffers. ↩

-

And conversely, the PGCOPY header is specific to the COPY command we executed to get a bulk response. ↩

-

We have some experience with the PostgreSQL wire protocol, too. ↩