A Practical Dive Into Late Materialization in arrow-rs Parquet Reads

Published

11 Dec 2025

By

Qiwei Huang and Andrew Lamb

Translations

简体中文

This article dives into the decisions and pitfalls of implementing Late Materialization in the Apache Parquet reader from arrow-rs (the reader powering Apache DataFusion among other projects). We'll see how a seemingly humble file reader requires complex logic to evaluate predicates—effectively becoming a tiny query engine in its own right.

1. Why Late Materialization?

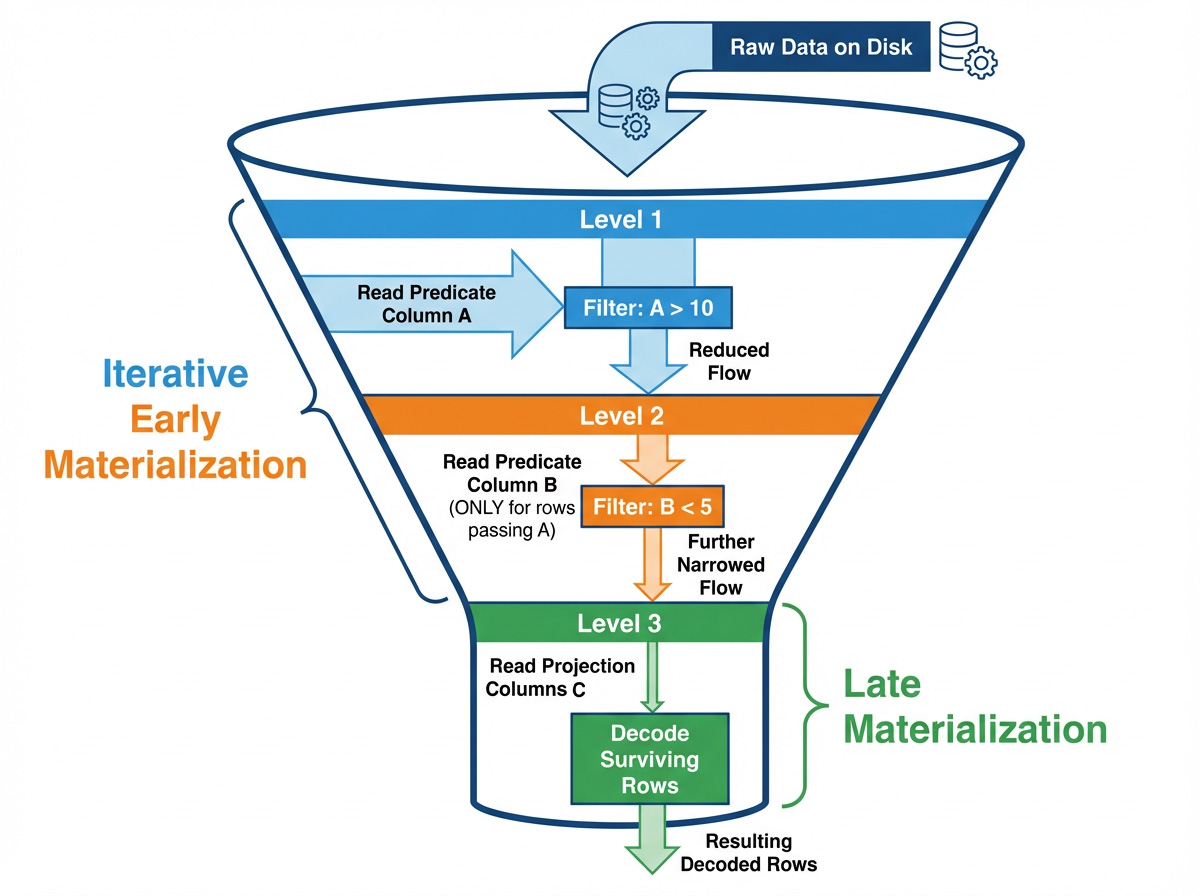

Columnar reads are a constant battle between I/O bandwidth and CPU decode costs. While skipping data is generally good, the act of skipping itself carries a computational cost. The goal of the Parquet reader in arrow-rs is pipeline-style late materialization: evaluate predicates first, then access projected columns. For predicates that filter many rows, materializing after evaluation minimizes reads and decode work.

The approach closely mirrors the LM-pipelined strategy from Materialization Strategies in a Column-Oriented DBMS by Abadi et al.: interleaving predicates and data column access instead of reading all columns at once and trying to stitch them back together into rows.

To evaluate a query like SELECT B, C FROM table WHERE A > 10 AND B < 5 using late materialization, the reader follows these steps:

- Read column

Aand evaluateA > 10to build aRowSelection(a sparse mask) representing the initial set of surviving rows. - Use that

RowSelectionto read surviving values of columnBand evaluateB < 5and update theRowSelectionto make it even sparser. - Use the refined

RowSelectionto read columnC(a projection column), decoding only the final surviving rows.

The rest of this post zooms in on how the code makes this path work.

2. Late Materialization in the Rust Parquet Reader

2.1 LM-pipelined

"LM-pipelined" might sound like something from a textbook. In arrow-rs, it simply refers to a pipeline that runs sequentially: "read predicate column → generate row selection → read data column". This contrasts with a parallel strategy, where all predicate columns are read simultaneously. While parallelism can maximize multi-core CPU usage, the pipelined approach is often superior in columnar storage because each filtering step drastically reduces the amount of data subsequent steps need to read and parse.

The code is structured into a few core roles:

- ReadPlan / ReadPlanBuilder: Encodes "which columns to read and with what row subset" into a plan. It does not pre-read all predicate columns. It reads one, tightens the selection, and then moves on.

-

RowSelection: Two implementations: use Run-length encoding (RLE) (via

RowSelector) to "skip/select N rows", or use an ArrowBooleanBufferbitmask to filter rows. This is the core mechanism that carries sparsity through the pipeline. -

ArrayReader: Responsible for decoding. It receives a

RowSelectionand decides which pages to read and which values to decode.

RowSelection can switch dynamically between RLE and bitmasks. Bitmasks are faster when gaps are tiny and sparsity is high; RLE is friendlier to large, page-level skips. Details on this trade-off appear in section 3.1.

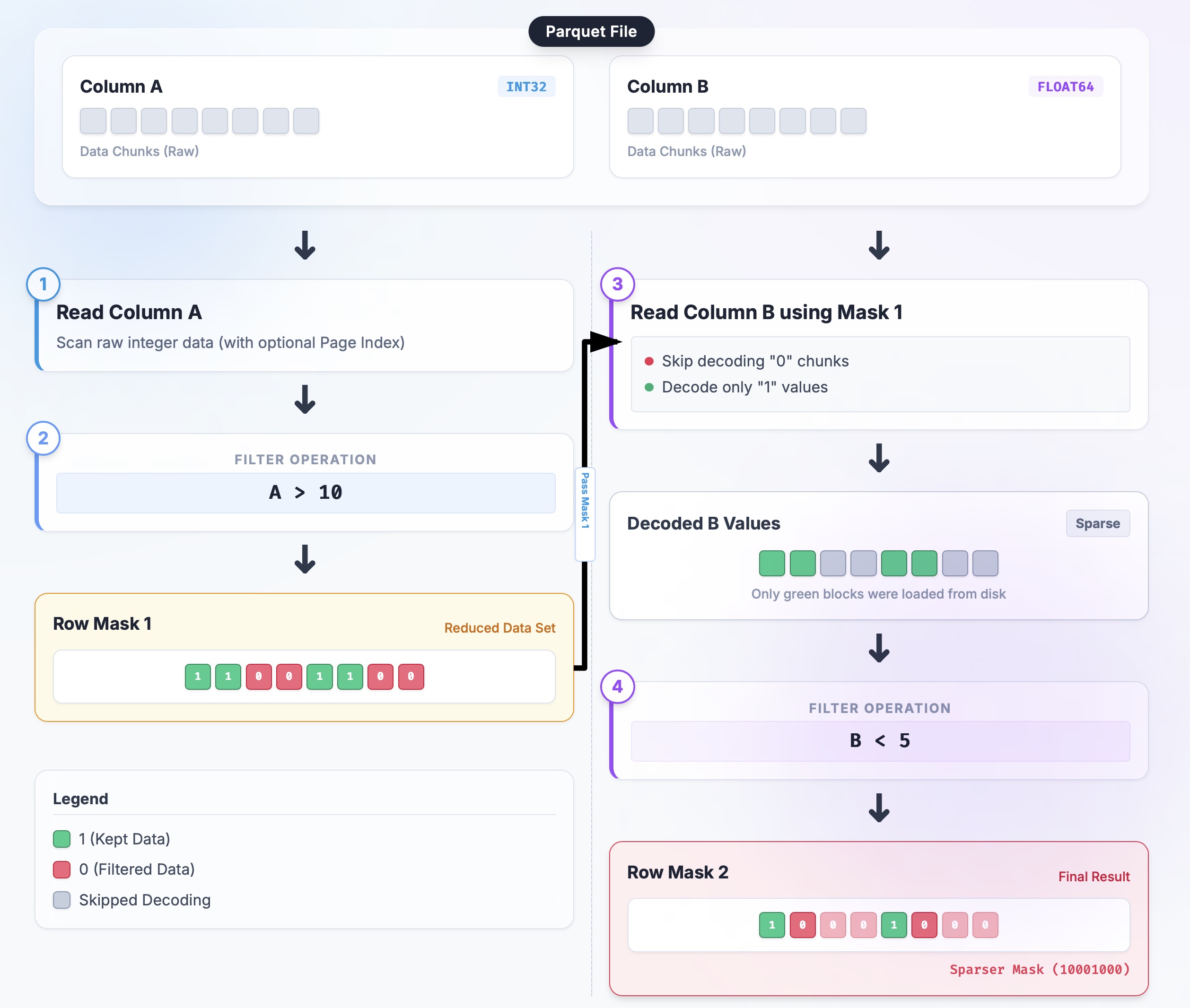

Consider again the query: SELECT B, C FROM table WHERE A > 10 AND B < 5:

-

Initial:

selection = None(equivalent to "select all"). -

Read A:

ArrayReaderdecodes column A in batches; the predicate builds a boolean mask;RowSelection::from_filtersturns it into a sparse selection. -

Tighten:

ReadPlanBuilder::with_predicatechains the new mask viaRowSelection::and_then. -

Read B: Build column B's reader with the current

selection; the reader only performs I/O and decoding for selected rows, producing an even sparser mask. -

Merge:

selection = selection.and_then(selection_b); projection columns now decode a tiny row set.

Code locations and sketch:

// Close to the flow in read_plan.rs (simplified)

let mut builder = ReadPlanBuilder::new(batch_size);

// 1) Inject external pruning (e.g., Page Index):

builder = builder.with_selection(page_index_selection);

// 2) Append predicates serially:

for predicate in predicates {

builder = builder.with_predicate(predicate); // internally uses RowSelection::and_then

}

// 3) Build readers; all ArrayReaders share the final selection strategy

let plan = builder.build();

let reader = ParquetRecordBatchReader::new(array_reader, plan);

I've drawn a simple flowchart that illustrates this flow to help you understand:

Now that you understand how this pipeline works, the next question is how to represent and combine these sparse selections (the Row Mask in the diagram), which is where RowSelection comes in.

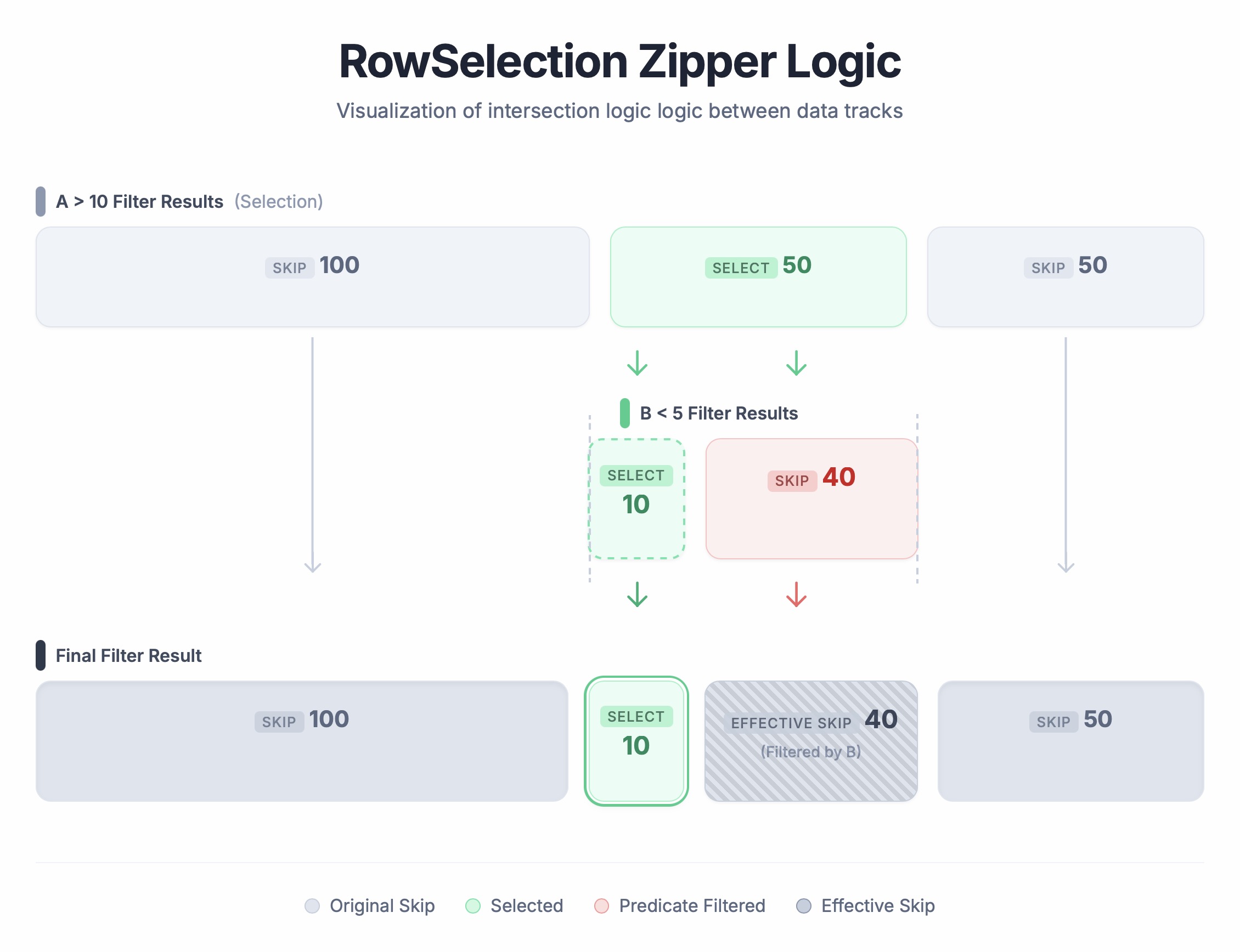

2.2 Combining row selectors (RowSelection::and_then)

RowSelection represents the set of rows that will eventually be produced. It currently uses RLE (RowSelector::select/skip(len)) to describe sparse ranges. RowSelection::and_then is the core operator for "apply one selection to another": the left-hand argument is "rows already passed" and the right-hand argument is "which of the passed rows also pass the second filter." The output is their boolean AND.

Walkthrough Example:

-

Input Selection A (already filtered):

[Skip 100, Select 50, Skip 50](physical rows 100-150 are selected) -

Selection B (filters within A):

[Select 10, Skip 40](within the 50 selected rows, only the first 10 survive B) -

Result:

[Skip 100, Select 10, Skip 90].

How it runs: Think of it like a zipper: we traverse both lists simultaneously, as shown below:

- First 100 rows: A is Skip → result is Skip 100.

-

Next 50 rows: A is Select. Look at B:

- B's first 10 are Select → result Select 10.

- B's remaining 40 are Skip → result Skip 40.

- Final 50 rows: A is Skip → result Skip 50.

Result: [Skip 100, Select 10, Skip 90].

Here is an example in code:

// Example: Skip 100 rows, then take the next 10

let a: RowSelection = vec![RowSelector::skip(100), RowSelector::select(50)].into();

let b: RowSelection = vec![RowSelector::select(10), RowSelector::skip(40)].into();

let result = a.and_then(&b);

// Result should be: Skip 100, Select 10, Skip 40

assert_eq!(

Vec::<RowSelector>::from(result),

vec![RowSelector::skip(100), RowSelector::select(10), RowSelector::skip(40)]

);

This keeps narrowing the filter while touching only lightweight metadata—no data copies. The current implementation of and_then is a two-pointer linear scan; complexity is linear in the number of selector segments. The more predicates shrink the selection, the cheaper later scans become.

3. Engineering Challenges

Late Materialization sounds simple enough in theory, but implementing it in a production-grade system like arrow-rs is an absolute engineering nightmare. Historically, these techniques are so tricky they have been locked away in proprietary engines. In the open source world, we've been grinding away at this for years (just look at the DataFusion ticket), and finally, we can flex our muscles and go toe-to-toe with full materialization. To pull this off, we had to tackle several serious engineering challenges.

3.1 Adaptive RowSelection Policy (Bitmask vs. RLE)

One major hurdle is choosing the right internal representation for RowSelection because the best choice depends on the sparsity pattern. This paper reveals a critical hurdle: there is no 'one-size-fits-all' format for RowSelection. The researchers found that the optimal internal representation is a moving target, shifting constantly depending on the sparsity pattern—essentially, how 'dense' or 'sparse' the surviving data is at any given moment.

- Ultra sparse (e.g., 1 row every 10,000): Using a bitmask here is just wasteful (1 bit per row adds up), whereas RLE is super clean—just a few selectors and you're done.

- Sparse but with tiny gaps (e.g., "read 1, skip 1"): RLE creates a fragmented mess that makes the decoder work overtime; here, bitmasks are way more efficient.

Since both have their pros and cons, we decided to get the best of both worlds with an adaptive strategy (see #arrow-rs/8733 for more details):

- We look at the average run length of the selectors and compare it to a threshold (currently

32). If the average is too small, we switch to bitmasks; otherwise, we stick with selectors (RLE). -

The Safety Net: Bitmasks look great until you hit Page Pruning, which can cause a nasty "missing page" panic because the mask might blindly try to filter rows from pages that were never even read. The

RowSelectionlogic watches out for this recipe for disaster and forces a switch back to RLE to keep things from crashing (see 3.1.2).

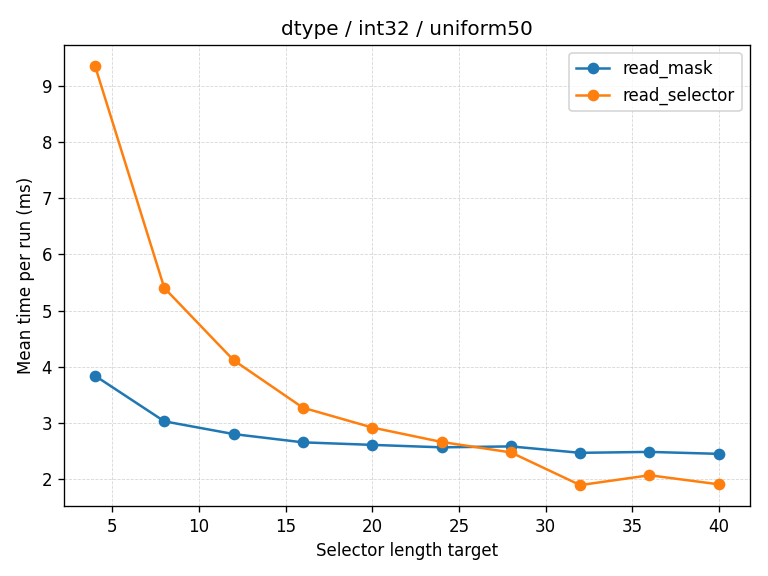

3.1.1 Where did the threshold of 32 come from?

The number 32 wasn't just pulled out of thin air. It came from a data-driven "face-off" using various distributions (even spacing, exponential sparsity, random noise). It does a solid job of distinguishing between "choppy but dense" and "long skip regions." In the future, we might get even fancier with heuristics based on data types.

The chart below shows an example run from the showdown. Blue lines are read_selector (RLE) and orange lines are read_mask (bitmasks). The vertical axis is time (lower is better), and the horizontal axis is average run length. You can see the performance curves cross around 32.

3.1.2 The Bitmask Trap: Missing Pages

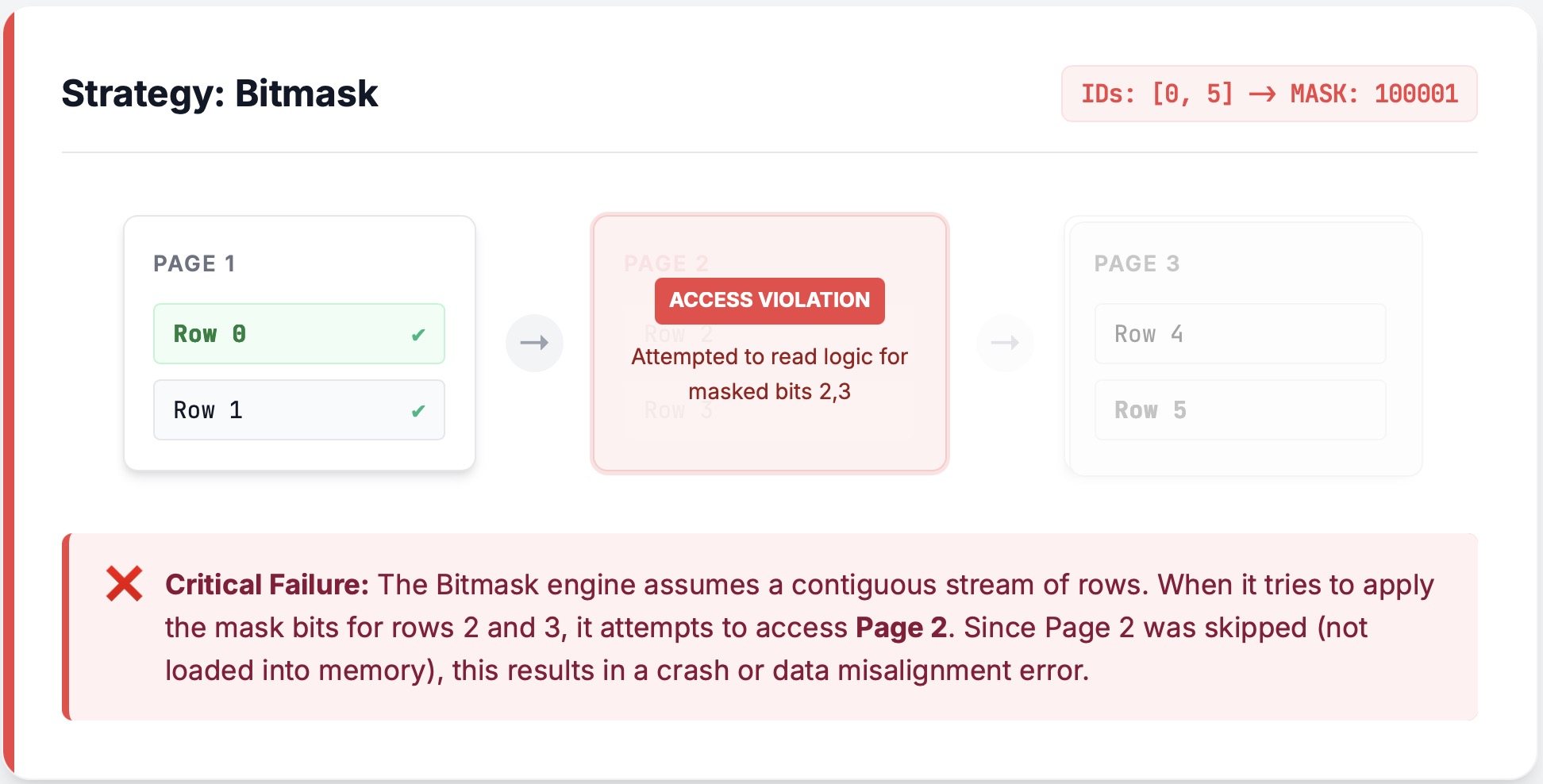

When implementing the adaptive strategy, bitmasks seem perfect on paper, but they hide a nasty trap when combined with Page Pruning.

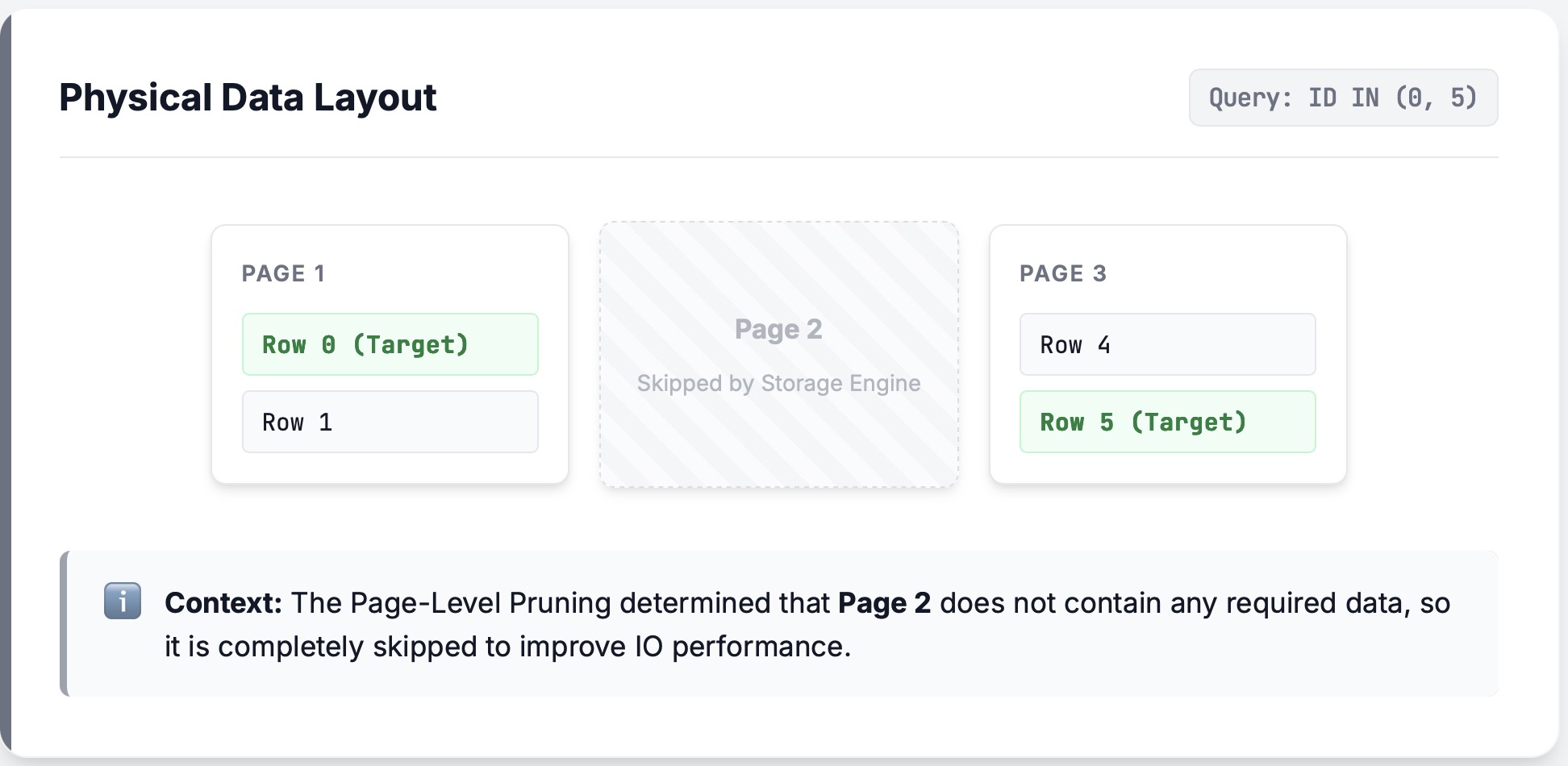

Before we get into the weeds, a quick refresher on pages (more in Section 3.2): Parquet files are sliced into pages. If we know a page has no rows in the selection, we don't even touch it—no decompression, no decoding. The ArrayReader doesn't even know it exists.

The Scene of the Crime:

Imagine reading a chunk of data and the middle four rows[0,1,2,3,4,5,6], [1,2,3,4], are filtered out. It just so happens that two of those rows, [2,3] sit in their own page, so that page gets completely pruned.

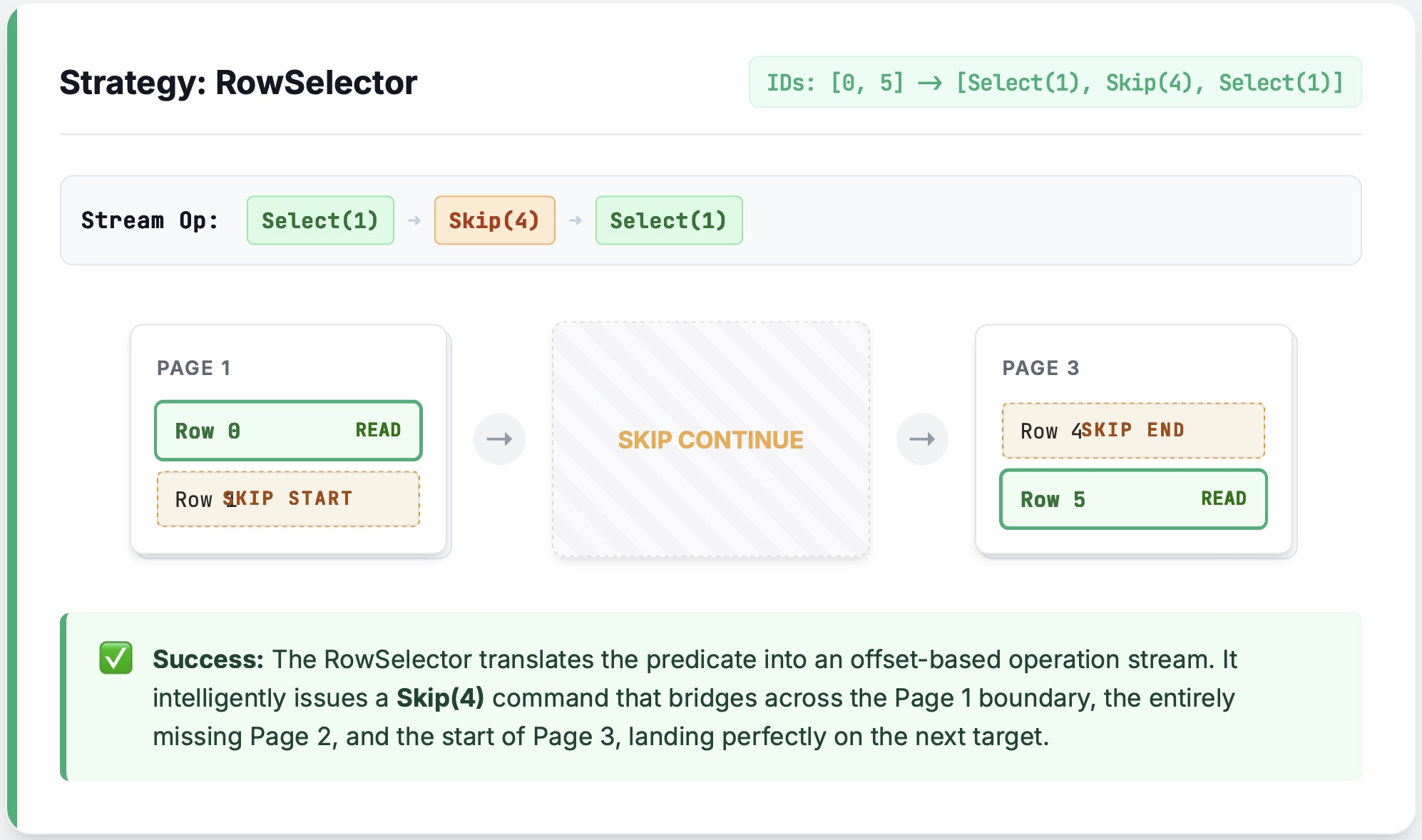

If we use RLE (RowSelector), executing Skip(4) is smooth sailing: we just jump over the gap.

The Problem:

If we use a bitmask, however, the reader will decode all 6 rows first, intending to filter them later. But that middle page isn't there! As soon as the decoder hits that gap, it panics. The ArrayReader is a stream processing unit—it doesn't handle I/O and thus doesn't know the layer above decided to prune a page, so it can't see the cliff coming.

The Fix:

Our current solution is conservative but bulletproof: if we detect Page Pruning, we ban bitmasks and force a fallback to RLE. In the future, we hope to extend the bitmask logic to be Page Pruning-aware (see #arrow-rs/8845).

// Auto prefers bitmask, but... wait, offset_index says page pruning is on.

let policy = RowSelectionPolicy::Auto { threshold: 32 };

let plan_builder = ReadPlanBuilder::new(1024).with_row_selection_policy(policy);

let plan_builder = override_selector_strategy_if_needed(

plan_builder,

&projection_mask,

Some(offset_index), // page index enables page pruning

);

// ...so we play it safe and switch to Selectors (RLE).

assert_eq!(plan_builder.row_selection_policy(), &RowSelectionPolicy::Selectors);

3.2 Page Pruning

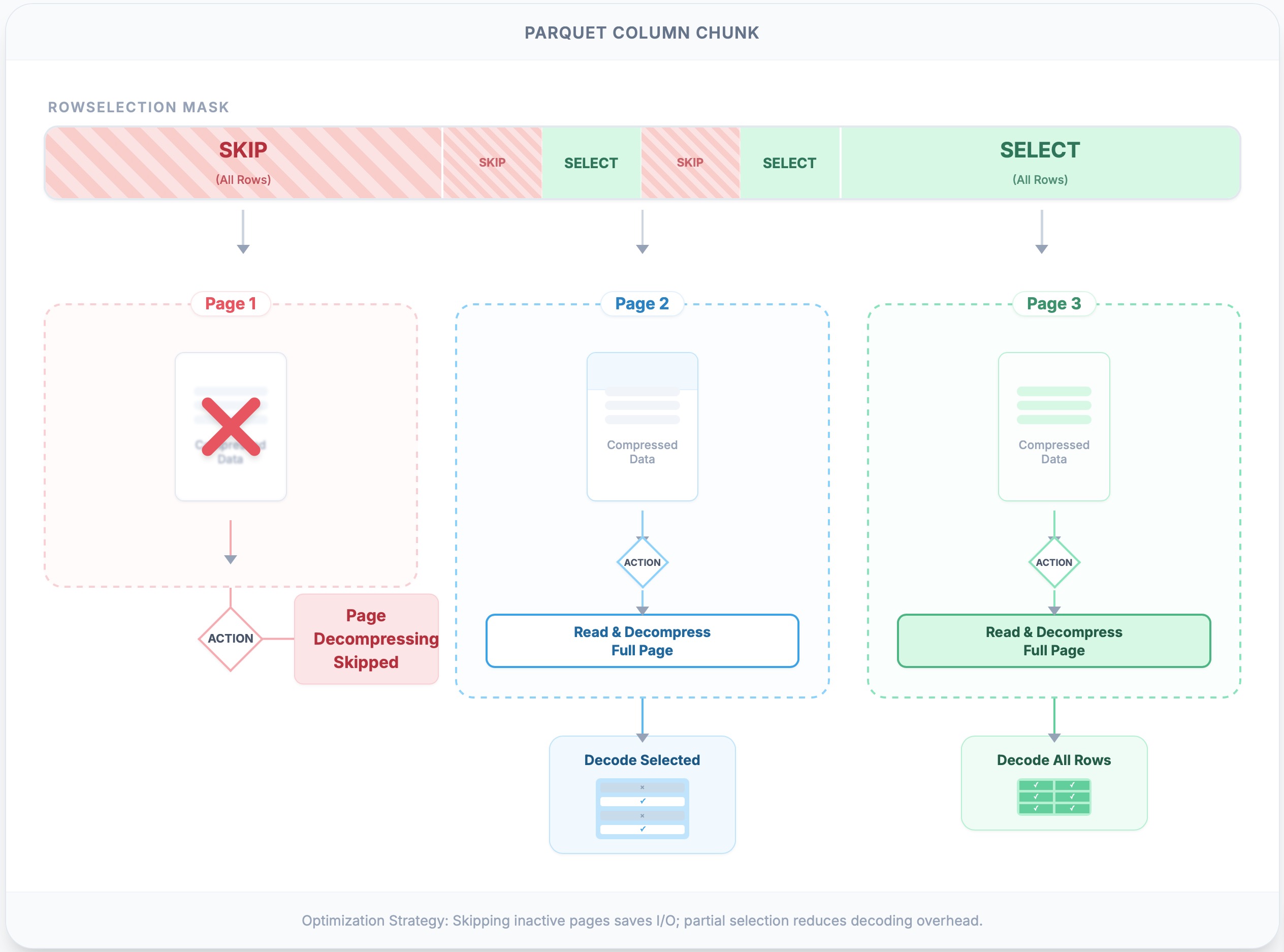

The ultimate performance win is not doing I/O or decoding at all. In the real world (especially with object storage), firing off a million tiny read requests is a performance killer. arrow-rs uses the Parquet PageIndex to calculate exactly which pages contain data we actually need. For very selective predicates, skipping pages can result in substantial I/O savings, even if the underlying storage client merges adjacent range requests. Another major win is reduced CPU: we completely skip the heavy lifting of decompressing and decoding entirely pruned pages.

-

The Catch: If the

RowSelectionselects even a single row from a page, the whole page must be decompressed. Therefore, the efficiency of this step relies heavily on the correlation between data clustering and the predicates. -

Implementation:

RowSelection::scan_rangescrunches the numbers using each page's metadata (first_row_indexandcompressed_page_size) to figure out which ranges are total skips, returning only the required(offset, length)list.

Page skipping is illustrated in the following code example:

// Example: two pages; page0 covers 0..100, page1 covers 100..200

let locations = vec![

PageLocation { offset: 0, compressed_page_size: 10, first_row_index: 0 },

PageLocation { offset: 10, compressed_page_size: 10, first_row_index: 100 },

];

// RowSelection wants 150..160; page0 is total junk, only read page1

let sel: RowSelection = vec![

RowSelector::skip(150),

RowSelector::select(10),

RowSelector::skip(40),

].into();

let ranges = sel.scan_ranges(&locations);

assert_eq!(ranges.len(), 1); // Only request page1

The following figure illustrates page skipping with RLE selections. The first page is neither read nor decoded, as no rows are selected. The second page is read and fully decompressed (e.g., zstd), and then only the needed rows are decoded. The third page is decompressed and decoded in full, as all rows are selected.

This mechanism acts as the bridge between logical row filtering and physical byte fetching. While we cannot slice the file thinner than a single page (due to compression boundaries), Page Pruning ensures that we never pay the decompression cost for a page unless it contributes at least one row to the result. It strikes a pragmatic balance: utilizing the coarse-grained Page Index to skip large swathes of data, while leaving the fine-grained RowSelection to handle the specific rows within the surviving pages.

3.3 Smart Caching

Late materialization introduces a structural Catch-22: to efficiently skip data, we must first read it. Consider a query like SELECT A FROM table WHERE A > 10. The reader must decode column A to evaluate the filter. In a traditional "read-everything" approach, this wouldn't be an issue: column A would simply sit in memory, waiting to be projected. However, in a strict pipeline, the "Predicate" stage and the "Projection" stage are decoupled. Once the filter produces a RowSelection, the projection stage sees that it needs column A and triggers a second read of the same data.

Without intervention, we pay a "double tax": decoding once to decide what to keep, and decoding again to actually keep it.CachedArrayReader, introduced in #arrow-rs/7850, solves this dilemma using a Dual-Layer Cache architecture. It allows us to stash the decoded batch the first time we see it (during filtering) and reuse it later (during projection).

But why two layers? Why not just one big cache?

- The Shared Cache (Optimistic Reuse): This is a global cache shared across all columns and readers. It has a user-configurable memory limit (capacity). When a page is decoded for a predicate, it is placed here. If the projection step runs soon after, it can "hit" this cache and avoid I/O. However, because memory is finite, cache eviction can happen at any moment. If we relied solely on this, a heavy workload could evict our data right before we need it again.

- The Local Cache (Deterministic Guarantee): This is a private cache specific to a single column's reader. It acts as a safety net. When a column is being actively read, the data is "pinned" in the Local Cache. This guarantees that the data remains available for the duration of the current operation, immune to eviction from the global Shared Cache.

The reader follows a strict hierarchy when fetching a page:

- Check Local: Do I already have it pinned?

- Check Shared: Did another part of the pipeline decode this recently? If yes, promote it to Local (pin it).

- Read from Source: Perform the I/O and decoding, then insert into both Local and Shared.

This dual strategy gives us the best of both worlds: the efficiency of sharing data between filter and projection steps, and the stability of knowing that necessary data won't vanish mid-query due to memory pressure.

3.4 Minimizing Copies and Allocations

Another area where arrow-rs has significant optimization is avoiding unnecessary copies. Rust's memory safe design makes it easy to copy, but every extra allocation wastes CPU cycles and memory bandwidth. A naive implementation often pays an "unnecessary tax" by decompressing data into a temporary Vec and then memcpy-ing it into an Arrow Buffer.

For fixed-width types (like integers or floats), this is completely redundant because their memory layouts are identical. PrimitiveArrayReader eliminates this overhead via zero-copy conversions: instead of copying bytes, it simply hands over ownership of the decoded Vec<T> directly to the underlying Arrow Buffer.

3.5 The Alignment Gauntlet

Chained filtering is a hair-pulling exercise in coordinate systems. "Row 1" in filter N might actually be "Row 10,001" in the file due to prior filters.

-

How do we keep the train on the rails?: We fuzz test every

RowSelectionoperation (split_off,and_then,trim). We need absolute certainty that our translation between relative and absolute offsets is pixel-perfect. This correctness is the bedrock that keeps the Reader stable under the triple threat of batch boundaries, sparse selections, and page pruning.

4. Conclusion

The Parquet reader in arrow-rs isn't just a humble file reader—it's a mini query engine in disguise. We've baked in high-end features like predicate pushdown and late materialization. The reader reads only what's needed and decodes only what's necessary, saving resources while maintaining correctness. Previously, these features were restricted to proprietary or tightly integrated systems. Now, thanks to the community's efforts, arrow-rs brings the benefits of advanced query processing techniques to even lightweight applications.

We invite you to join the community, explore the code, experiment with it, and contribute to its ongoing evolution. The journey of optimizing data access is never-ending, and together, we can push the boundaries of what's possible in open-source data processing.