Recent Improvements to Hash Join in Arrow C++

Published

18 Jul 2025

By

Rossi Sun (zanmato)

Editor’s Note: Apache Arrow is an expansive project, ranging from the Arrow columnar format itself, to its numerous specifications, and a long list of implementations. Arrow is also an expansive project in terms of its community of contributors. In this blog post, we’d like to highlight recent work by Apache Arrow Committer Rossi Sun on improving the performance and stability of Arrow’s embeddable query execution engine: Acero.

Introduction

Hash join is a fundamental operation in analytical processing engines — it matches rows from two tables based on key values using a hash table for fast lookup. In the C++ implementation of Apache Arrow, the hash join is implemented in the C++ engine Acero, which powers query execution in bindings like PyArrow and the R Arrow package. Even if you haven't used Acero directly, your code may already be benefiting from it under the hood.

For example, this simple PyArrow example uses Acero:

import pyarrow as pa

t1 = pa.table({'id': [1, 2, 3],

'year': [2020, 2022, 2019]})

t2 = pa.table({'id': [3, 4],

'n_legs': [5, 100],

'animal': ["Brittle stars", "Centipede"]})

t1.join(t2, 'id').combine_chunks().sort_by('year')

Acero was originally created in 2019 to demonstrate that the ever-growing library of compute kernels in Arrow C++ could be linked together into realistic workflows and also to take advantage of the emerging Datasets API to give these workflows access to data. Rather than aiming to compete with full query engines like DuckDB, Acero focuses on enabling flexible, composable, and embeddable query execution — serving as a building block for tools and systems that need fast, modular analytics capabilities — including those built atop Arrow C++, or integrating via bindings like PyArrow, Substrait, or ADBC.

Across several recent Arrow C++ releases, we've made substantial improvements to the hash join implementation to address common user pain points. These changes improve stability, memory efficiency, and parallel performance, with a focus on making joins more usable and scalable out of the box. If you've had trouble using Arrow’s hash join in the past, now is a great time to try again.

Scaling Safely: Improvements to Stability

In earlier versions of Arrow C++, the hash join implementation used internal data structures that weren’t designed for very large datasets and lacked safeguards in some of the underlying memory operations. These limitations rarely surfaced in small to medium workloads but became problematic at scale, manifesting as crashes or subtle correctness issues.

At the core of Arrow’s join implementation is a compact, row-oriented structure known as the “row table”. While Arrow’s data model is columnar, its hash join implementation operates in a row-wise fashion — similar to modern engines like DuckDB and Meta’s Velox. This layout minimizes CPU cache misses during hash table lookups by collocating keys, payloads, and null bits in memory so they can be accessed together.

In previous versions, the row table used 32-bit offsets to reference packed rows. This capped each table’s size to 4GB and introduced risks of overflow when working with large datasets or wide rows. Several reported issues — GH-34474, GH-41813, and GH-43202 — highlighted the limitations of this design. In response, PR GH-43389 widened the internal offset type to 64-bit, reworking key parts of the row table infrastructure to support larger data sizes more safely and scalably.

Besides the offset limitation, earlier versions of Arrow C++ also included overflow-prone logic in the buffer indexing paths used throughout the hash join implementation. Many internal calculations assumed that 32-bit integers were sufficient for addressing memory — a fragile assumption when working with large datasets or wide rows. These issues appeared not only in conventional C++ indexing code but also in Arrow’s SIMD-accelerated paths — Arrow includes heavy SIMD specializations, used to speed up operations like hash table probing and row comparison. Together, these assumptions led to subtle overflows and incorrect behavior, as documented in issues like GH-44513, GH-45334, and GH-45506.

Two representative examples:

- Row-wise buffer access in C++

The aforementioned row table stores fixed-length data in tightly packed buffers. Accessing a particular row (and optionally a column within it) typically involves pointer arithmetic:

const uint8_t* row_ptr = row_ptr_base + row_length * row_id;

When both row_length and row_id are large 32-bit integers, their product can overflow.

Similarly, accessing null masks involves null-bit indexing arithmetic:

int64_t bit_id = row_id * null_mask_num_bytes * 8 + pos_after_encoding;

The intermediate multiplication is performed using 32-bit arithmetic and can overflow even though the final result is stored in a 64-bit variable.

- SIMD gathers with 32-bit offsets

One essential SIMD instruction is the AVX2 intrinsic __m256i _mm256_i32gather_epi32(int const * base, __m256i vindex, const int scale);, which performs a parallel memory gather of eight 32-bit integers based on eight 32-bit signed offsets. It was extensively used in Arrow for hash table operations, for example, fetching 8 group IDs (hash table slots) in parallel during hash table probing:

__m256i group_id = _mm256_i32gather_epi32(elements, pos, 1);

and loading 8 corresponding key values from the right-side input in parallel for comparison:

__m256i right = _mm256_i32gather_epi32((const int*)right_base, offset_right, 1);

If any of the computed offsets exceed 2^31 - 1, they wrap into the negative range, which can lead to invalid memory access (i.e., a crash) or, more subtly, fetch data from a valid but incorrect location — producing silently wrong results (trust me, you don’t want to debug that).

To mitigate these risks, PR GH-45108, GH-45336, and GH-45515 promoted critical arithmetic to 64-bit and reworked SIMD logic to use safer indexing. Buffer access logic was also encapsulated in safer abstractions to avoid repeated manual casting or unchecked offset math. These examples are not unique to Arrow — they reflect common pitfalls in building data-intensive systems, where unchecked assumptions about integer sizes can silently compromise correctness.

Together, these changes make Arrow’s hash join implementation significantly more robust and better equipped for modern data workloads. These foundations not only resolve known issues but also reduce the risk of similar bugs in future development.

Leaner Memory Usage

While refining overflow-prone parts of the hash join implementation, I ended up examining most of the code path for potential pitfalls. When doing this kind of work, one sits down quietly and interrogates every line — asking not just whether an intermediate value might overflow, but whether it even needs to exist at all. And during that process, I came across something unrelated to overflow — but even more impactful.

In a textbook hash join algorithm, once the right-side table (the build-side) is fully accumulated, a hash table is constructed to support probing the left-side table (the probe-side) for matches. To parallelize this build step, Arrow C++’s implementation partitions the build-side into N partitions — typically matching the number of available CPU cores — and builds a separate hash table for each partition in parallel. These are then merged into a final, unified hash table used during the probe phase.

The issue? The memory footprint. The total size of the partitioned hash tables is roughly equal to that of the final hash table, but they were being held in memory even after merging. Once the final hash table was built, these temporary structures had no further use — yet they persisted through the entire join operation. There were no crashes, no warnings, no visible red flags — just silent overhead.

Once spotted, the fix was straightforward: restructure the join process to release these buffers immediately after the merge. The change was implemented in PR GH-45552. The memory profiles below illustrate its impact.

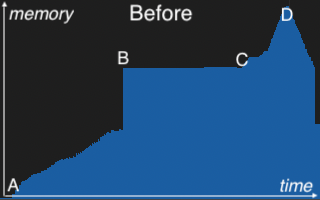

At A, memory usage rises steadily as the join builds partitioned hash tables in parallel. B marks the merge point, where these partitions are combined into a final, unified hash table. C represents the start of the probe phase, where the left-side table is scanned and matched against the final hash table. Memory begins to rise again as join results are materialized. D is the peak of the join operation, just before memory begins to drop as processing completes. The “leap of faith” occurs at the star on the right profile, where the partitioned hash tables are released immediately after merging. This early release frees up substantial memory and makes room for downstream processing — reducing the overall peak memory observed at D.

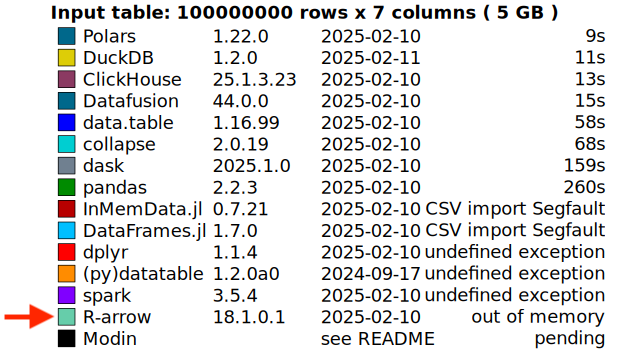

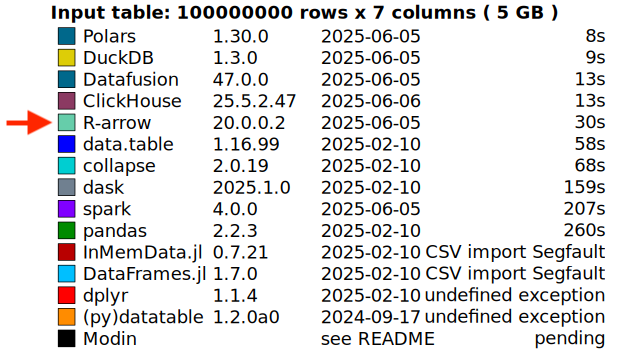

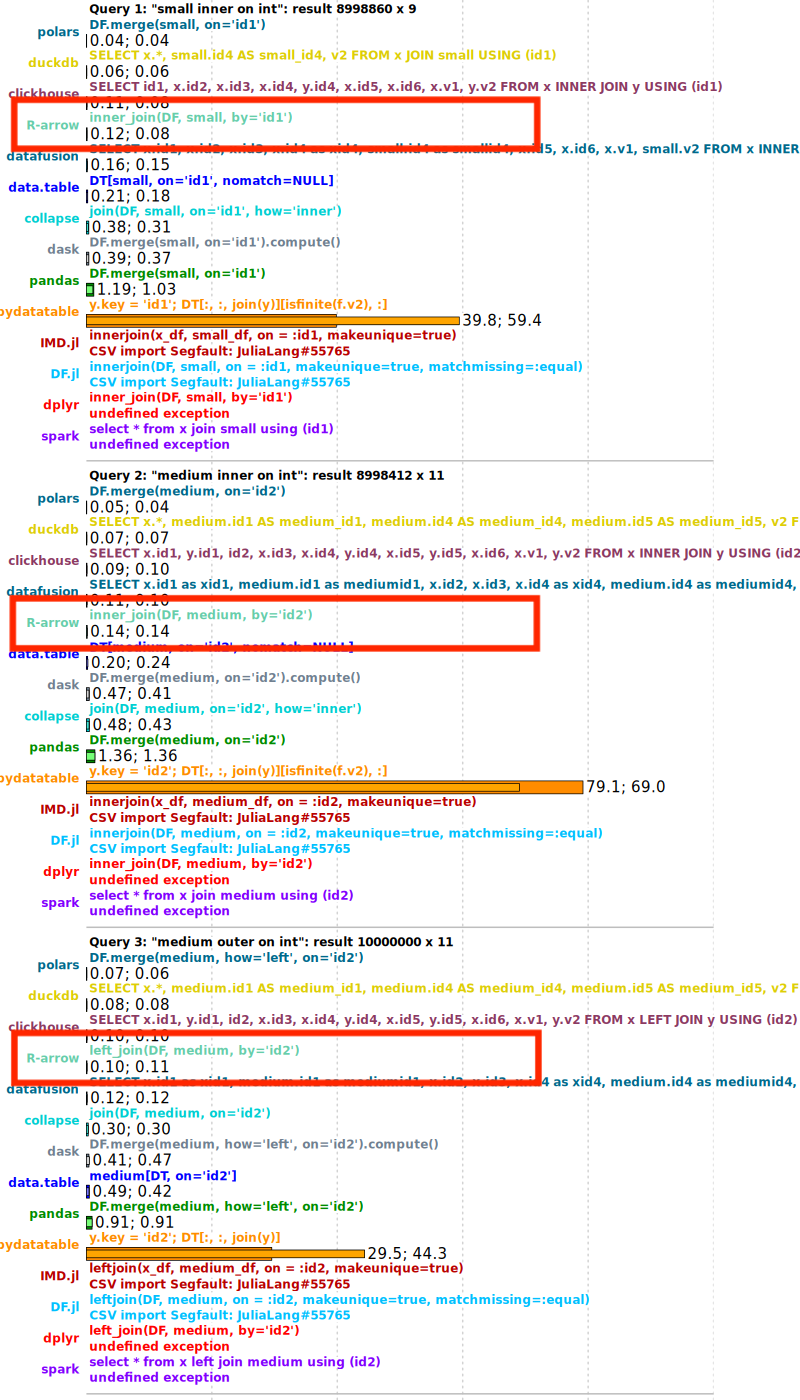

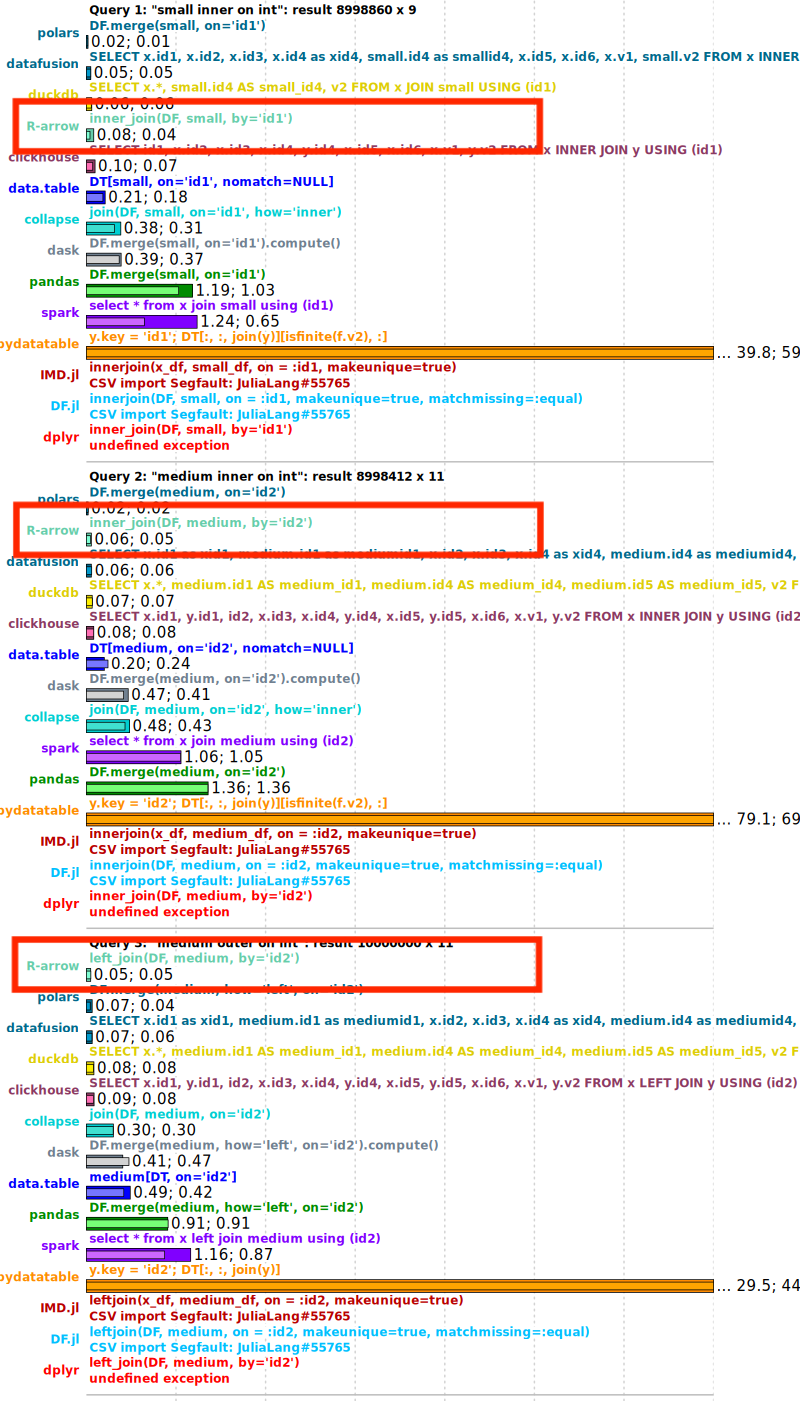

This improvement already benefits real-world scenarios — for example, the DuckDB Labs DB Benchmark. Some benchmark queries that previously failed with out-of-memory (OOM) errors can now complete successfully — as shown in the comparison below.

As one reviewer noted in the PR, this was a “low-hanging fruit.” And sometimes, meaningful performance gains don’t come from tuning hot loops or digging through flame graphs — they come from noticing something that doesn’t feel right and asking: why are we still keeping this around?

Faster Execution Through Better Parallelism

Not every improvement comes from poring over flame graphs — but some definitely do. Performance is, after all, the most talked-about aspect of any query engine. So, how about a nice cup of flame graph?

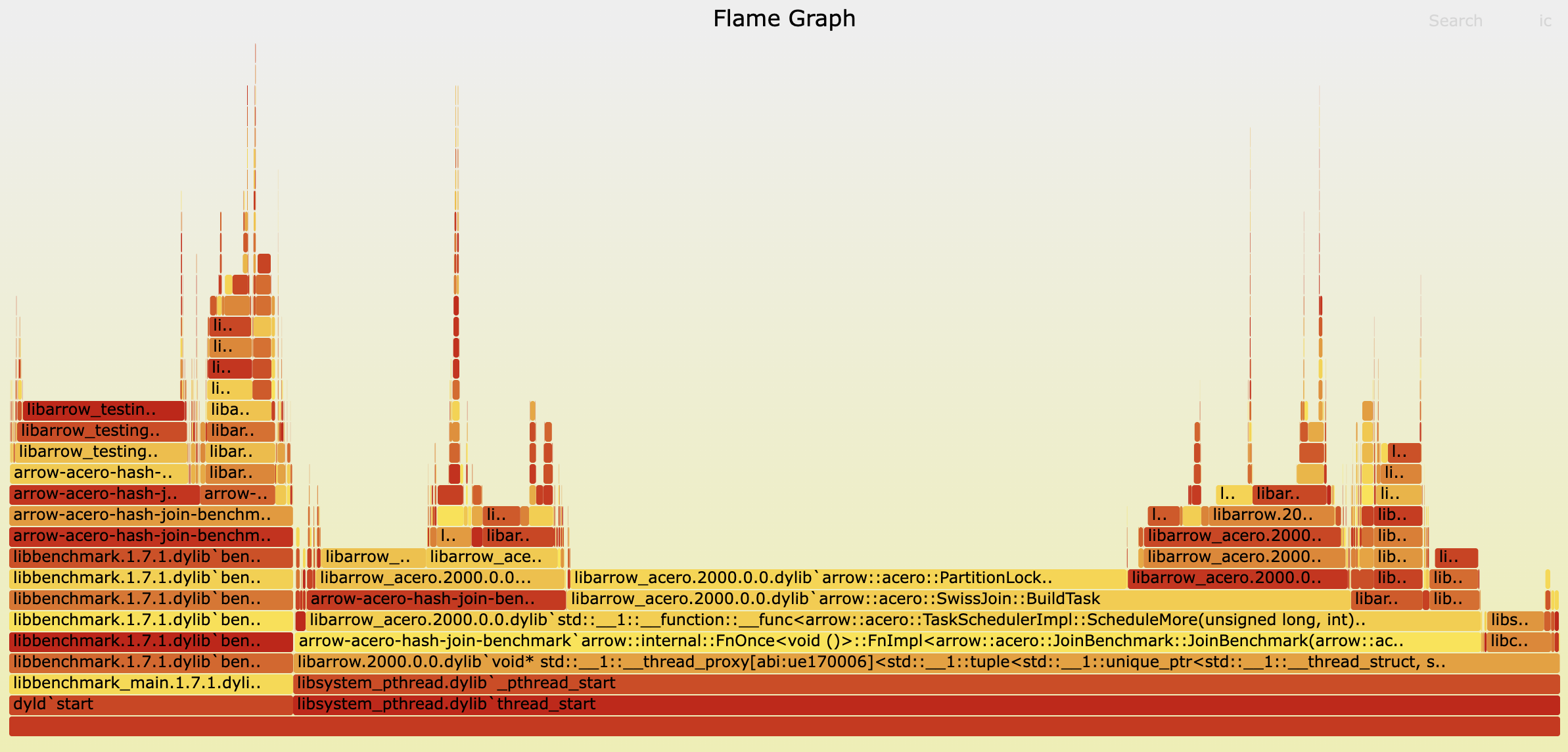

It’s hard not to notice the long, flat bar dominating the middle — especially with the rather alarming word “Lock” in it. That’s our red flag.

We’ve mentioned that in the build phase, we build partitioned hash tables in parallel. In earlier versions of Arrow C++, this parallelism was implemented on a batch basis — each thread processed a build-side batch concurrently. Since each batch contained arbitrary data that could fall into any partition, threads had to synchronize when accessing shared partitions. This was managed through locks on partitions. Although we introduced some randomness in the locking order to reduce contention, it remained high — clearly visible in the flame graph.

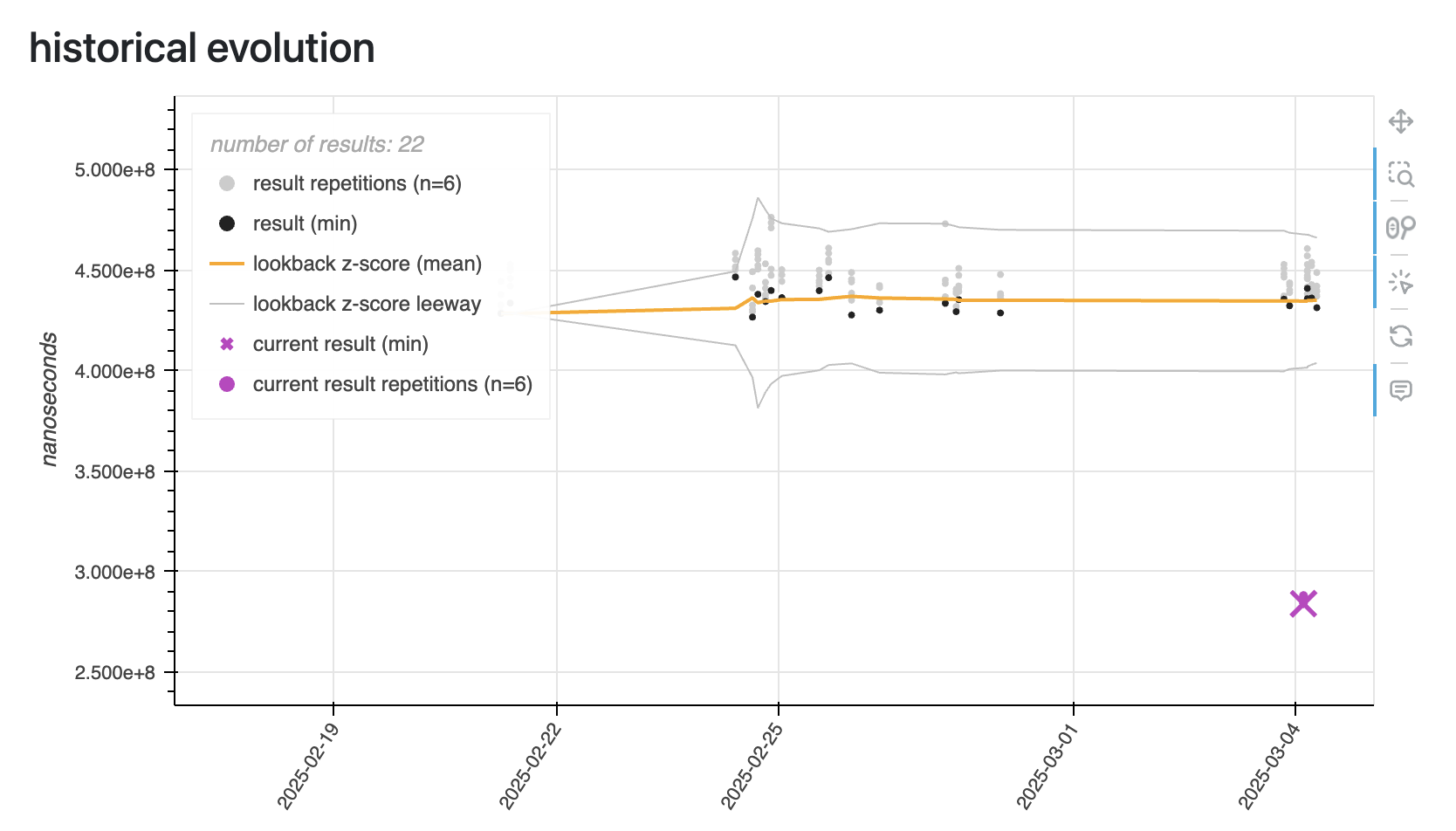

To mitigate this contention, we restructured the build phase in PR GH-45612. Instead of having all threads partition and insert at once — each thread touching every hash table — we split the work into two distinct stages. In the first partition stage, M threads take their assigned batches and only partition them, recording which rows belong to which partition. No insertion happens yet — just classification. Then comes the second, newly separated build stage. Here, N threads take over, and each thread is responsible for building just one of the N partitioned hash tables. Every thread scans all the relevant partitions across all batches but inserts only the rows belonging to its assigned partition. This restructuring eliminates the need for locking between threads during insertion — each thread now has exclusive access to its partitioned hash table. By decoupling the work this way, we turned a highly contentious operation into a clean, embarrassingly parallel one. As a result, we saw performance improve by up to 10x in dedicated build benchmarks. The example below is from a more typical, general-purpose workload — not especially build-heavy — but it still shows a solid 2x speedup. In the chart, the leap of faith — marked by the purple icons 🟣⬇️ — represents results with this improvement applied, while the gray and black ones show earlier runs before the change.

Also in real-world scenarios like the DuckDB Labs DB Benchmark, we’ve observed similar gains. The comparison below shows around a 2x improvement in query performance after this change was applied.

Additional improvements include GH-43832, which extends AVX2 acceleration to more probing code paths, and GH-45918, which introduces parallelism to a previously sequential task phase. These target more specialized scenarios and edge cases.

Closing

These improvements reflect ongoing investment in Arrow C++’s execution engine and a commitment to delivering fast, robust building blocks for analytic workloads. They are available in recent Arrow C++ releases and exposed through higher-level bindings like PyArrow and the Arrow R package — starting from version 18.0.0, with the most significant improvements landing in 20.0.0. If joins were a blocker for you before — due to memory, scale, or correctness — recent changes may offer a very different experience.

The Arrow C++ engine is not just alive — it’s improving in meaningful, user-visible ways. We’re also actively monitoring for further issues and open to expanding the design based on user feedback and real-world needs. If you’ve tried joins in the past and run into performance or stability issues, we encourage you to give them another try and file an issue on GitHub if you run into any issues.

If you have any questions about this blog post, please feel free to contact the author, Rossi Sun.