Our journey at F5 with Apache Arrow (part 2): Adaptive Schemas and Sorting to Optimize Arrow Usage

Published

26 Jun 2023

By

Laurent Quérel

In the previous article, we discussed our use of Apache Arrow within the context of the OpenTelemetry project. We investigated various techniques to maximize the efficiency of Apache Arrow, aiming to find the optimal balance between data compression ratio and queryability. The compression results speak for themselves, boasting improvements ranging from 1.5x to 5x better than the original OTLP protocol. In this article, we will delve into three techniques that have enabled us to enhance both the compression ratio and memory usage of Apache Arrow buffers within the current version of the OTel Arrow protocol.

The first technique we'll discuss aims to optimize schemas in terms of memory usage. As you'll see, the gains can be substantial, potentially halving memory usage in certain cases. The second section will delve more deeply into the various approaches that can be used to handle recursive schema definitions. Lastly, we'll emphasize that the design of your schema(s), coupled with the sorts you can apply at the record level, play a pivotal role in maximizing the benefits of Apache Arrow and its columnar representation.

Handling dynamic and unknown data distributions

In certain contexts, the comprehensive definition of an Arrow schema can end up being overly broad and complex in order to cover all possible cases that you intend to represent in columnar form. However, as is often the case with complex schemas, only a subset of this schema will actually be utilized for a specific deployment. Similarly, it's not always possible to determine the optimal dictionary encoding for one or more fields in advance. Employing a broad and very general schema that covers all cases is usually more memory-intensive. This is because, for most implementations, a column without value still continues to consume memory space. Likewise, a column with dictionary encoding that indexes a uint64 will occupy four times more memory than the same column with a dictionary encoding based on a uint8.

To illustrate this more concretely, let's consider an OTel collector positioned at the output of a production environment, receiving a telemetry data stream produced by a large and dynamic set of servers. Invariably, the content of this telemetry stream will change in volume and nature over time. It's challenging to predict the optimal schema in such a scenario, and it's equally difficult to know in advance the distribution of a particular attribute of the telemetry data passing through this point.

To optimize such scenarios, we have adopted an intermediary approach that we have named dynamic Arrow schema, aiming to gradually adapt the schema based on the observed data. The general principle is relatively simple. We start with a general schema defining the maximum envelope of what should be represented. Some fields of this schema will be declared optional, while other fields will be encoded with multiple possible options depending on the observed distribution. In theory, this principle can be applied to other types of transformations (e.g., recursive column creation) but we will let your imagination explore these other options. So if you encounter data streams where certain fields are not utilized, some union variants remain unused, and/or the value distribution of a field cannot be determined a priori, it may be worthwhile to invest time in implementing this model. This can lead to improved efficiency in terms of compression ratio, memory usage, and processing speed.

The following Go Arrow schema definition provides an example of such a schema, instrumented with a collection of annotations. These annotations will be processed by an enhanced Record Builder, equipped with the ability to dynamically adapt the schema. The structure of this system is illustrated in Figure 1.

var (

// Arrow schema for the OTLP Arrow Traces record (without attributes, links, and events).

TracesSchema = arrow.NewSchema([]arrow.Field{

// Nullabe:true means the field is optional, in this case of 16 bit unsigned integers

{Name: constants.ID, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint16, Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.Resource, Type: arrow.StructOf([]arrow.Field{

{Name: constants.ID, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint16, Nullable: true},

// --- Use dictionary with 8 bit integers initially ----

{Name: constants.SchemaUrl,Type: arrow.BinaryTypes.String,Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.DroppedAttributesCount,Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint32,Nullable: true},

}...), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.Scope, Type: arrow.StructOf([]arrow.Field{

{Name: constants.ID, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint16, Metadata: acommon.Metadata(acommon.DeltaEncoding), Nullable: true},

// --- Use dictionary with 8 bit integers initially ----

{Name: constants.Name, Type: arrow.BinaryTypes.String, Metadata: acommon.Metadata(acommon.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.Version, Type: arrow.BinaryTypes.String, Metadata: acommon.Metadata(acommon.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.DroppedAttributesCount, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint32, Nullable: true},

}...), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.SchemaUrl, Type: arrow.BinaryTypes.String, Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.StartTimeUnixNano, Type: arrow.FixedWidthTypes.Timestamp_ns},

{Name: constants.DurationTimeUnixNano, Type: arrow.FixedWidthTypes.Duration_ms, Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8)},

{Name: constants.TraceId, Type: &arrow.FixedSizeBinaryType{ByteWidth: 16}},

{Name: constants.SpanId, Type: &arrow.FixedSizeBinaryType{ByteWidth: 8}},

{Name: constants.TraceState, Type: arrow.BinaryTypes.String, Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.ParentSpanId, Type: &arrow.FixedSizeBinaryType{ByteWidth: 8}, Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.Name, Type: arrow.BinaryTypes.String, Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8)},

{Name: constants.KIND, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Int32, Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.DroppedAttributesCount, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint32, Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.DroppedEventsCount, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint32, Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.DroppedLinksCount, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint32, Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.Status, Type: arrow.StructOf([]arrow.Field{

{Name: constants.StatusCode, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Int32, Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.StatusMessage, Type: arrow.BinaryTypes.String, Metadata: schema.Metadata(schema.Dictionary8), Nullable: true},

}...), Nullable: true},

}, nil)

)

In this example, Arrow field-level metadata are employed to designate when a field is optional (Nullable: true) or to specify the minimal dictionary encoding applicable to a particular field (Metadata Dictionary8/16/…). Now let’s imagine a scenario utilizing this schema in a straightforward scenario, wherein only a handful of fields are actually in use, and the cardinality of most dictionary-encoded fields is low (i.e., below 2^8). Ideally, we'd want a system capable of dynamically constructing the following simplified schema, which, in essence, is a strict subset of the original schema.

var (

// Simplified schema definition generated by the Arrow Record encoder based on

// the data observed.

TracesSchema = arrow.NewSchema([]arrow.Field{

{Name: constants.ID, Type: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint16, Nullable: true},

{Name: constants.StartTimeUnixNano, Type: arrow.FixedWidthTypes.Timestamp_ns},

{Name: constants.TraceId, Type: &arrow.FixedSizeBinaryType{ByteWidth: 16}},

{Name: constants.SpanId, Type: &arrow.FixedSizeBinaryType{ByteWidth: 8}},

{Name: constants.Name, Type: &arrow.DictionaryType {

IndexType: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint8,

ValueType: arrow.BinaryTypes.String}},

{Name: constants.KIND, Type: &arrow.DictionaryType {

IndexType: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Uint8,

ValueType: arrow.PrimitiveTypes.Int32,

}, Nullable: true},

}, nil)

)

Additionally, we desire a system capable of automatically adapting the aforementioned schema if it encounters new fields or existing fields with a cardinality exceeding the size of the current dictionary definition in future batches. In extreme scenarios, if the cardinality of a specific field surpasses a certain threshold, we would prefer the system to automatically revert to the non-dictionary representation (mechanism of dictionary overflow). That is precisely what we will elaborate on in the remainder of this section.

An overview of the different components and events used to implement this approach is depicted in figure 1.

The overall Adaptive Arrow schema component takes a data stream segmented into batches and produces one or multiple streams of Arrow Records (one schema per stream). Each of these records is defined with an Arrow schema, which is based both on the annotated Arrow schema and the shape of fields observed in the incoming data.

More specifically, the process of the Adaptive Arrow schema component consists of four main phases

Initialization phase

During the initialization phase, the Arrow Record Encoder reads the annotated Arrow schema (i.e. the reference schema) and generates a collection of transformations. When these transformations are applied to the reference schema, they yield the first minimal Arrow schema that adheres to the constraints depicted by these annotations. In this initial iteration, all optional fields are eliminated, and all dictionary-encoded fields are configured to utilize the smallest encoding as defined by the annotation (only Dictionary8 in the previous example). These transformations form a tree, reflecting the structure of the reference schema.

Feeding phase

Following the initialization is the feeding phase. Here, the Arrow Record Encoder scans the batch and attempts to store all the fields in an Arrow Record Builder, which is defined by the schema created in the prior step. If a field exists in the data but is not included in the schema, the encoder will trigger a missing field event. This process continues until the current batch is completely processed. An additional internal check is conducted on all dictionary-encoded fields in the Arrow Record builder to ensure there’s no dictionary overflow (i.e. more unique entries than the cardinality of the index permits). Dictionary overflow events are generated if such a situation is detected. Consequently, by the end, all unknown fields and dictionary overflow would have been detected, or alternatively, no discrepancies would have surfaced if the data aligns perfectly with the schema.

Corrective phase

If at least one event has been generated, a corrective phase will be initiated to fix the schema. This optional stage considers all the events generated in the previous stage and adjusts the transformation tree accordingly to align with the observed data. A missing field event will remove a NoField transformation for the corresponding field. A dictionary overflow event will modify the dictionary transformation to mirror the event (e.g. changing the index type from uint8 to uint16, or if the maximum index size has been reached, the transformation will remove the dictionary-encoding and revert to the original non-dictionary-encoded type). The updated transformation tree is subsequently used to create a new schema and a fresh Arrow Record Builder. This Record Builder is then utilized to replay the preceding feeding phase with the batch that wasn’t processed correctly.

Routing phase

Once a Record Builder has been properly fed, an Arrow Record is created, and the system transitions into the routing phase. The router component calculates a schema signature of the record and utilizes this signature to route the record to an existing Arrow stream compatible with the signature, or it initiates a new stream if there is no match.

This four-phase process should gradually adapt and stabilize the schema to a structure and definition that is optimized for a specific data stream. Unused fields will never unnecessarily consume memory. Dictionary-encoded fields will be defined with the most optimal index size based on the observed data cardinality, and fields with a cardinality exceeding a certain threshold (defined by configuration) will automatically revert to their non-dictionary-encoded versions.

To effectively execute this approach, you must ensure that there is a sufficient level of flexibility on the receiver side. It's crucial that your downstream pipeline remains functional even when some fields are missing in the schema or when various dictionary index configurations are employed. While this may not always be feasible without implementing additional transformations upon reception, it proves worthwhile in certain scenarios.

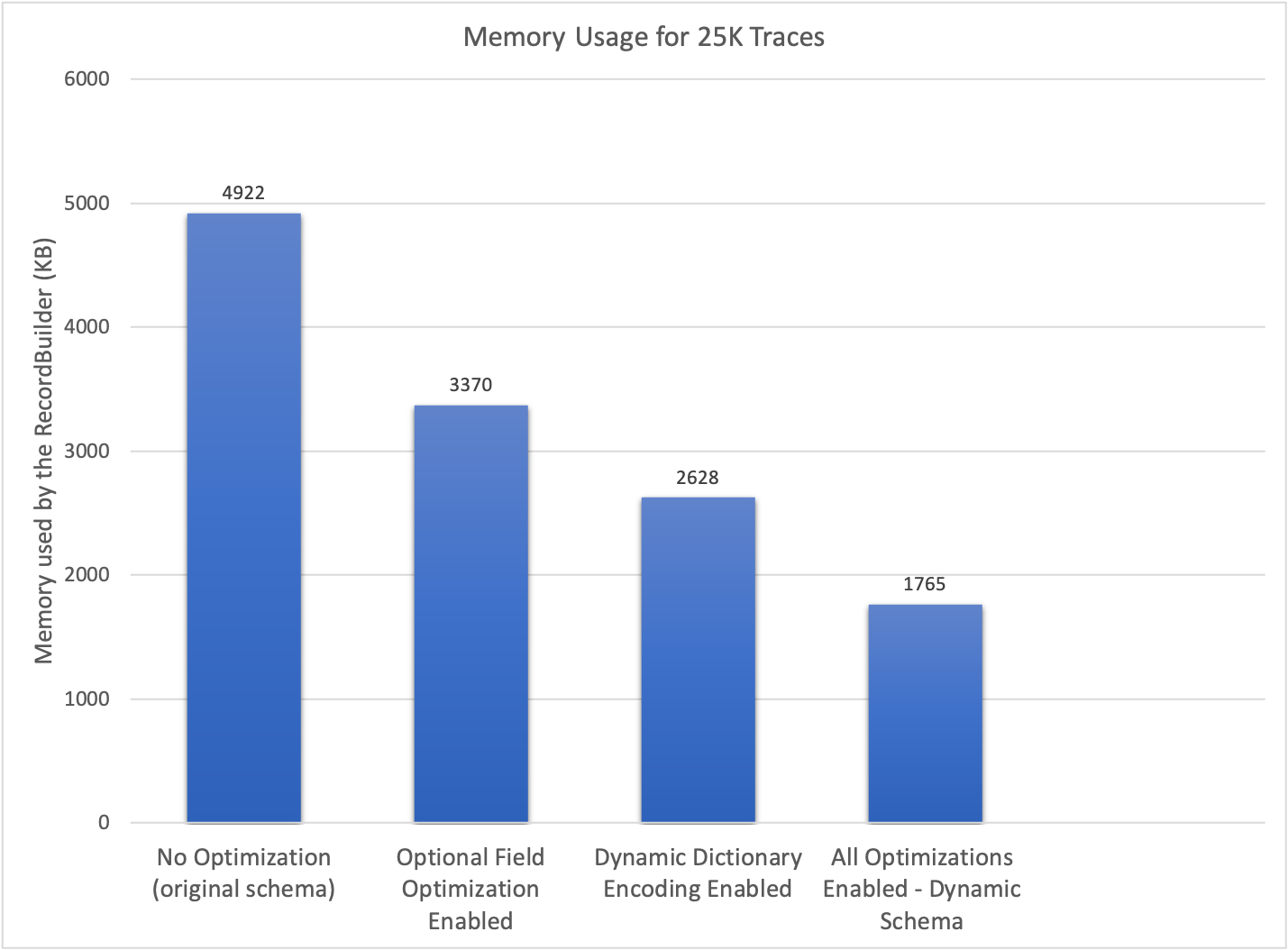

The following results highlight the significant memory usage reduction achieved through the application of various optimization techniques. These results were gathered using a schema akin to the one previously presented. The considerable memory efficiency underscores the effectiveness of this approach.

The concept of a transformation tree enables a generalized approach to perform various types of schema optimizations based on the knowledge acquired from the data. This architecture is highly flexible; the current implementation allows for the removal of unused fields, the application of the most specific dictionary encoding, and the optimization of union type variants. In the future, there is potential for introducing additional optimizations that can be expressed as transformations on the initial schema. An implementation of this approach is available here.

Handling recursive schema definition

Apache Arrow does not support recursive schema definitions, implying that data structures with variable depth cannot be directly represented. Figure 3 exemplifies such a recursive definition where the value of an attribute can either be a simple data type, a list of values, or a map of values. The depth of this definition cannot be predetermined.

Several strategies can be employed to circumvent this limitation. Technically, the dynamic schema concept we've presented could be expanded to dynamically update the schema to include any missing level of recursion. However, for this use case, this method is complex and has the notable downside of not offering any assurance on the maximum size of the schema. This lack of constraint can pose security issues; hence, this approach isn't elaborated upon.

The second approach consists of breaking the recursion by employing a serialization format that supports the definition of a recursive schema. The result of this serialization can then be integrated into the Arrow record as a binary type column, effectively halting the recursion at a specific level. To fully leverage the advantages of columnar representation, it is crucial to apply this ad-hoc serialization as deeply within the data structure as feasible. In the context of OpenTelemetry, this is performed at the attribute level – more specifically, at the second level of attributes.

A variety of serialization formats, such as protobuf or CBOR, can be employed to encode recursive data. Without particular treatment, these binary columns may not be easily queryable by the existing Arrow query engines. Therefore, it's crucial to thoughtfully ascertain when and where to apply such a technique. While I'm not aware of any attempts to address this limitation within the Arrow system, it doesn't seem insurmountable and would constitute a valuable extension. This would help reduce the complexity of integrating Arrow with other systems that rely on such recursive definitions.

Importance of sorting

In our preceding article, we explored a variety of strategies to represent hierarchical data models, including nested structures based on struct/list/map/union, denormalization and flattening representations, as well as a multi-record approach. Each method presents its unique advantages and disadvantages. However, in this last section, we'll delve deeper into the multi-record approach, focusing specifically on its ability to offer versatile sorting options and how these options contribute to an enhanced compression ratio.

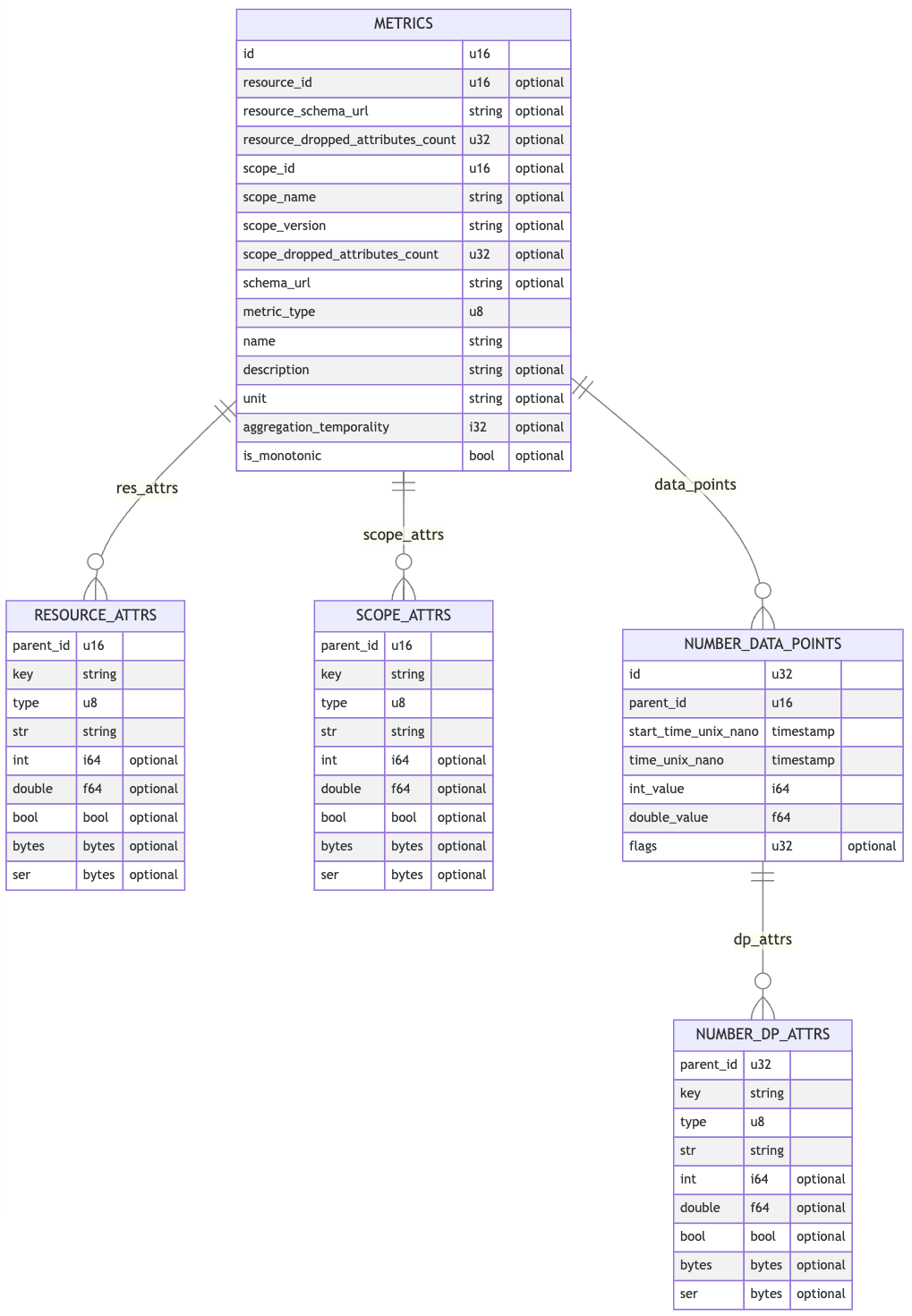

In the OTel Arrow protocol, we leverage the multi-record approach to represent metrics, logs, and traces. The following entity-relationship diagram offers a simplified version of various record schemas and illustrates their relationships, specifically those used to represent gauges and sums. A comprehensive description of the Arrow data model employed in OpenTelemetry can be accessed here.

These Arrow records, also referred to as tables, form a hierarchy with METRICS acting as the primary entry point. Each table can be independently sorted according to one or more columns. This sorting strategy facilitates the grouping of duplicated data, thereby improving the compression ratio.

The relationship between the primary METRICS table and the secondary RESOURCE_ATTRS, SCOPE_ATTRS, and NUMBER_DATA_POINTS tables is established through a unique id in the main table and a parent_id column in each of the secondary tables. This {id,parent_id} pair represents an overhead that should be minimized to the greatest extent possible post-compression.

To achieve this, the ordering process for the different tables adheres to the hierarchy, starting from the main table down to the leaf. The main table is sorted (by one or multiple columns), and then an incremental id is assigned to each row. This numerical id is stored using delta-encoding, which is implemented on top of Arrow.

The secondary tables directly connected to the main table are sorted using the same principle, but the parent_id column is consistently utilized as the last column in the sort statement. Including the parent_id column in the sort statement enables the use of a variation of delta encoding. The efficiency of this approach is summarized in the chart below.

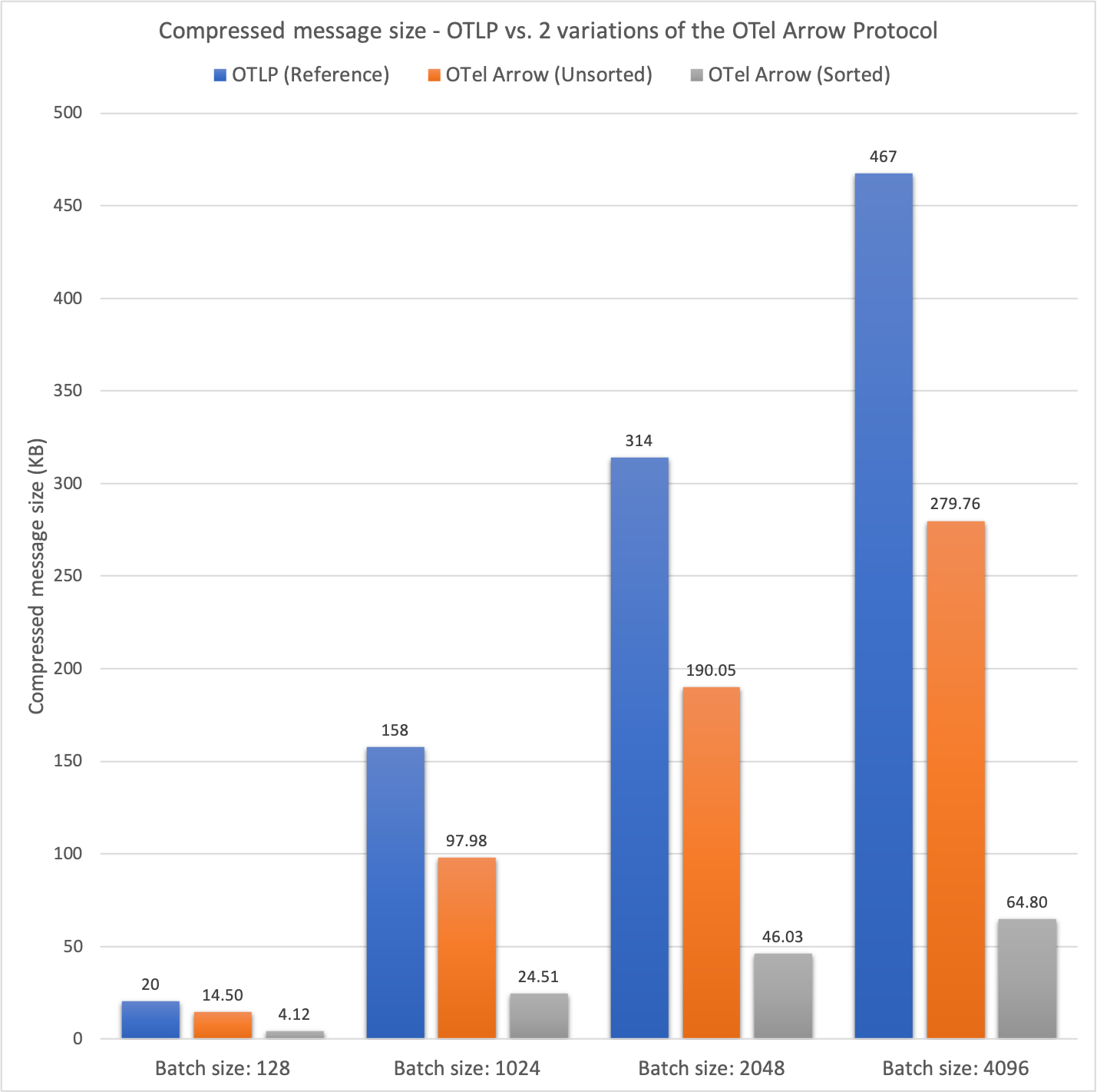

The second column presents the average size of the OTLP batch both pre- and post-ZSTD compression for batches of varying sizes. This column serves as a reference point for the ensuing two columns. The third column displays results for the OTel Arrow protocol without any sorting applied, while the final column showcases results for the OTel Arrow protocol with sorting enabled.

Before compression, the average batch sizes for the two OTel Arrow configurations are predictably similar. However, post-compression, the benefits of sorting each individual table on the compression ratio become immediately apparent. Without sorting, the OTel Arrow protocol exhibits a compression ratio that's 1.40 to 1.67 times better than the reference. When sorting is enabled, the OTel Arrow protocol outperforms the reference by a factor ranging from 4.94 to 7.21 times!

The gains in terms of compression obviously depend on your data and the redundancy of information present in your data batches. According to our observations, the choice of a good sort generally improves the compression ratio by a factor of 1.5 to 8.

Decomposing a complex schema into multiple simpler schemas to enhance sorting capabilities, coupled with a targeted approach to efficiently encode the identifiers representing the relationships, emerges as an effective strategy for enhancing overall data compression. This method also eliminates complex Arrow data types, such as lists, maps, and unions. Consequently, it not only improves but also simplifies data query-ability. This simplification proves beneficial for existing query engines, which may struggle to operate on intricate schemas.

Conclusion and next steps

This article concludes our two-part series on Apache Arrow, wherein we have explored various strategies to maximize the utility of Apache Arrow within specific contexts. The adaptive schema architecture presented in the second part of this series paves the way for future optimization possibilities. We look forward to seeing what the community can add based on this contribution.

Apache Arrow is an exceptional project, continually enhanced by a thriving ecosystem. However, throughout our exploration, we have noticed certain gaps or points of friction that, if addressed, could significantly enrich the overall experience.

- Designing an efficient Arrow schema can, in some cases, prove to be a challenging task. Having the ability to collect statistics at the record level could facilitate this design phase (data distribution per field, dictionary stats, Arrow array sizes before/after compression, and so on). These statistics would also assist in identifying the most effective columns on which to base the record sorting.

- Native support for recursive schemas would also increase adoption by simplifying the use of Arrow in complex scenarios. While I'm not aware of any attempts to address this limitation within the Arrow system, it doesn't seem insurmountable and would constitute a valuable extension. This would help reduce the complexity of integrating Arrow with other systems that rely on such recursive definitions.

- Harmonizing the support for data types as well as IPC stream capabilities would also be a major benefit. Predominant client libraries support nested and hierarchical schemas, but their use is limited due to a lack of full support across the rest of the ecosystem. For example, list and/or union types are not well supported by query engines or Parquet bridges. Also, the advanced dictionary support within IPC streams is not consistent across different implementations (i.e. delta dictionaries and replacement dictionaries are not supported by all implementations).

- Optimizing the support of complex schemas in terms of memory consumption and compression rate could be improved by natively integrating the concept of the dynamic schema presented in this article.

- Detecting dictionary overflows (index level) is not something that is easy to test on the fly. The API could be improved to indicate this overflow as soon as an insertion occurs.

Our effort to utilize Apache Arrow in conjunction with OpenTelemetry has produced encouraging results. While this has necessitated considerable investment in terms of development, exploration, and benchmarking, we hope that these articles will aid in accelerating your journey with Apache Arrow. Looking ahead, we envision an end-to-end integration with Apache Arrow and plan to significantly extend our use of the Arrow ecosystem. This extension involves providing a bridge with Parquet and integrating with a query engine such as DataFusion, with the goal of processing telemetry streams within the collector.